Takahide Kiuchi’s View - Insight into Economic Trends: Financial Crises Appear in Different Forms at Different Times

With a series of mid-size bank failures occurring in the US this March, plus the acquisition of mismanaged Swiss financial giant Credit Suisse by its rival UBS in Europe, we are seeing uncertainties over banks exploding on a global scale. At present, the situation is slowly regaining stability, but I believe the crisis is not yet over. Although the European and US economies have remained relatively stable, if economic conditions were to deteriorate going forward, the US could potentially see a second round of banking insecurities in which anxieties over mid-size banks are compounded by financial market turmoil caused by a fund crisis.

Sudden outflows of deposits and three headwinds for US banks

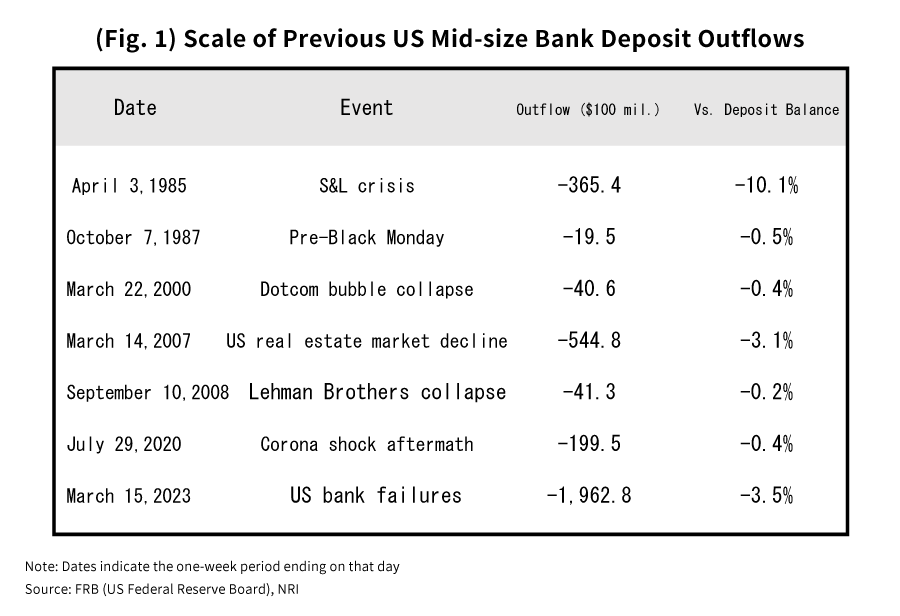

Looking back at the mounting banking worries in the US in March 2023, we see that the total outflow of deposits across all mid-size banks in the week of the failures came out to approximately $196 billion (around 26 trillion yen), reaching a scale never seen before. Even compared to various other past events, the value of these deposit outflows is significantly greater, and it briefly seemed as though the situation could have been deemed a banking crisis (Fig. 1).

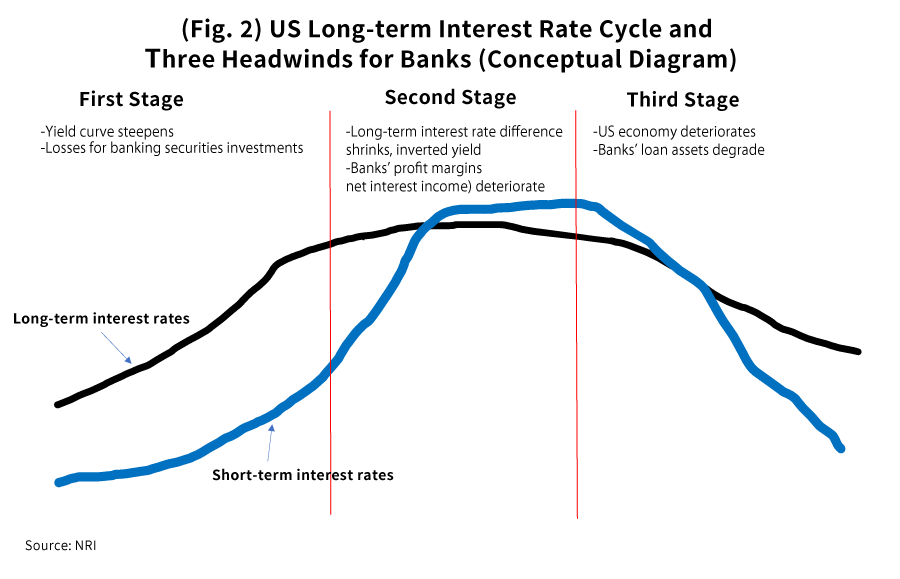

The impetus for these banking woes was the historic large-scale interest rate hikes enacted by the FRB (US Federal Reserve Board) with respect to policy interest rates. Long-term interest rates rose significantly to factor in future policy interest rate increases, causing unrealized losses in the securities on bank balance sheets to swell. This constitutes the first headwind for banks.

Furthermore, as the FRB went forward with hiking rates, it created a reversal phenomenon whereby short-term interest rates surpassed long-term ones, producing a so-called inverted yield curve. That inversion substantially shrinks the profit margins of banks that raise funds in the short term in order to conduct long-term fund management. This is the second headwind. These two strong headwinds for banks across the board set the stage for the banking worries that arose in March.

Moreover, the effects of lending constraints on banks in response to rapid rate hikes and these banking uncertainties could well lead the economy to deteriorate going forward. If that happens, then banks will likely suffer a third headwind in the form of a rise in bad debts. (Fig. 2)

Massive unrealized losses for securities and lending constraints bring risk of a credit crunch

According to the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation), the value of unrealized losses for securities owned by US banks (FDIC member banks) rose to $620 billion at the end of 2022. Of this amount, $341 billion are securities that are categorized as bonds held to maturity, which do not require mark-to-market accounting.

However, when there is a rapid outflow of deposits, banks become forced to sell securities carrying unrealized losses which are categorized as bonds held to maturity, in order to meet that demand. They incur tremendous losses in the course of doing so, which creates the risk that the equity capital supporting their business stability could suddenly decline. Such a situation is what in fact befell SVB (Silicon Valley Bank), which collapsed in March.

In terms of measuring the true stability of a bank’s operations, we should focus on its equity capital, which is obtained by subtracting the unrealized losses of the securities it owns as bonds held to maturity. If we try to calculate that amount, then the overall capital adequacy ratio of US banks which was publicly stated to be 14.9% at the end of 2022 would in fact be only 12.6%, more than two percentage points lower. This is near the 12.5% seen at the end of September 2008, immediately before the Lehman Brothers collapse that sparked the global financial crisis.

The IMF (International Monetary Fund) also calculated in the April edition of its Global Financial Stability Report that when the unrealized losses for securities owned by US banks are deducted from their equity capital, around 9% of mid-size or larger banks with assets worth between $10 billion and $300 billion are in fact undercapitalized.

The effects of the massive amount of unrealized losses for securities, I believe, is leading financial markets or bank customers to conclude that banks’ actual capital adequacy ratios are lower than they appear, and that these institutions are at heightened solvency risk.

Bank lending beginning to be curtailed (credit crunch)

That being the case, we can expect that in order to raise their capital adequacy ratios, enhance their operational stability, and regain the trust of their customers and the financial markets, banks will seek to move to curtail the risky assets that would be the denominator in calculating those ratios, and in particular their loan assets. This means a credit crunch. As a result, corporations and individuals will find it more difficult to raise capital, and economic activity will ultimately stagnate.

That will degrade the loan assets of the banks and cause their bad debts to grow. As a result, the banks’ profits will be squeezed, and their capital adequacy ratios will decline instead.

Thus, if individual banks move toward restraining lending all at once with the aim of restoring their business stability and trust, it could potentially end up putting pressure on their management. This is what is called the “fallacy of composition”. There is a possible risk that the banks themselves will bring about a second round of banking insecurities.

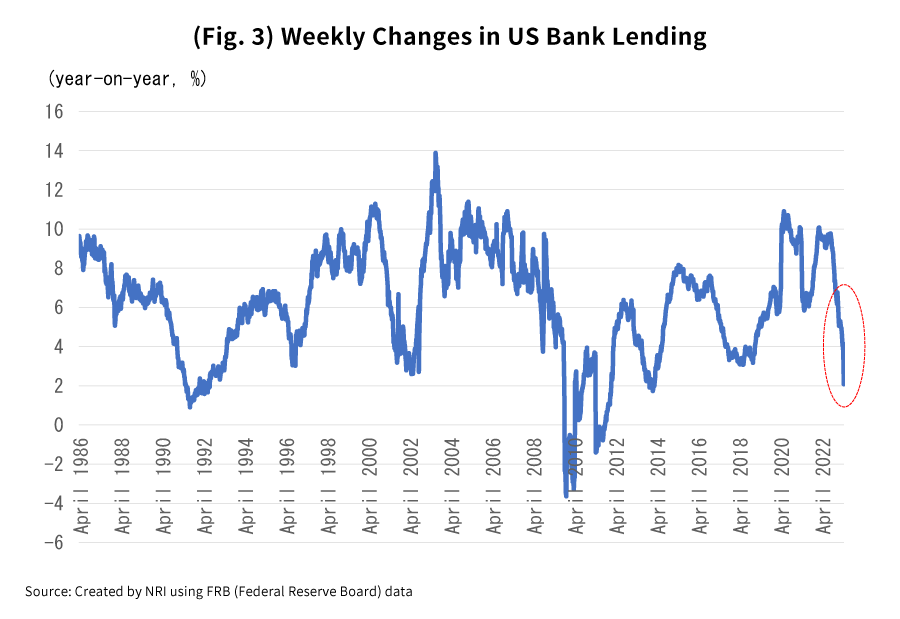

If we check how bank lending is trending now, we can see that in fact this activity is sharply slowing down. The total amount of outstanding loans by mid-size banks in the US in the week ending March 15 when the bank failures occurred was at roughly the same level as in the week prior, but in the week ending March 22 it was 1.2% lower compared to the week before, while in the week ending March 29 it was down 2.5%, indicating an accelerating contraction.

If we look at the overall banking picture including large institutions, the total amount of loans in the week ending March 29 was around 2% higher year-on-year, the lowest level seen in eight years, and it is expected that sooner or later, this amount will sink to the lowest levels seen since after the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008 (Fig. 3). The credit crunch trend has already begun.

The risk of a compound crisis involving a fund crisis

While it is conceivable that deteriorating economic conditions in the US could trigger a second round of banking woes, it could also bring about a separate problem. That would be a crisis involving non-bank financial intermediaries concerning investment trusts, ETFs (exchange-traded funds), MMFs (money market funds), life insurance, and pension funds, i.e., the so-called “shadow banking” system, and in particular, a crisis for open investment funds which can be terminated at any time.

According to the IMF, ever since the Lehman Brothers Collapse in 2008, the total amount of assets held by open investment funds has been growing rapidly, and in March 2022 it reached as high as $41 trillion. Some 60% of this amount was issued in the US.

If an economic downturn were to trigger the price of financial assets invested in by these open investment funds (which can be terminated any time) to fall, causing investment funds to suffer a drop in operational performance, it would spur their customers to withdraw their funds all at once. That would drive the funds to begin rapidly selling off their financial assets to obtain cash, and would deal a major blow to the financial markets. This would be a kind of bank run. If they cannot meet these withdrawal demands, then the funds could even collapse.

With the more speculative-grade asset classes targeted by investment funds like high-yield bonds and emerging market bonds, are difficult to sell, and a rush to sell off these assets at any cost tends to cause their prices to plummet. In other words, their liquidity is quite low.

A “liquidity mismatch” in which accumulated capital is highly liquid but investment targets have low liquidity could, at times of market stress, conceivably heighten the risk of investment fund collapses or financial market turmoil.

It's said that “financial crises appear in different forms at different times”. I don’t believe there will be another Lehman Brothers-type financial crisis in the future that will drive large US banks to the brink of collapse. The ones holding a lot of high-risk securitized instruments etc. now aren’t large banks as was true back then, but are in fact investment funds. The risk has now shifted to them.

If economic conditions worsen and cause corporate credit risks to rise, then the prices of high-yield bonds, securitized products for SME loans, and securitized products for commercial property lending would fall significantly, and this potentially could lead to an investment fund crisis.

The upcoming second round of banking uncertainties may be a new type of compound crisis, involving a combination of business difficulties for smaller banks resembling the S&L crisis of the 1980s (when many savings and loans failed after the real estate market went bust), an investment fund crisis, and concomitant chaos in the financial market.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.