Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends: Excessive Corporate Debt as the Achilles’ Heel of the US Economic and Financial System

Since last year, the US has embarked on a course of monetary tightening at an historic pace, but the economy has yet to slow down. Tightening tends to have deleterious effects on interest rate-sensitive housing investments and automobile purchases, and those effects can send the country into a recession by spreading to the economy as a whole, or so the pattern has typically gone in the past. However, this time that empirical rule has not been borne out, and while housing investments have continued to decline over the last two years, overall economic stability has not suffered any major collapse. One might suppose that this has much to do with the current state of individual debt in the US.

The US’ changing debt structure and the effects of monetary tightening

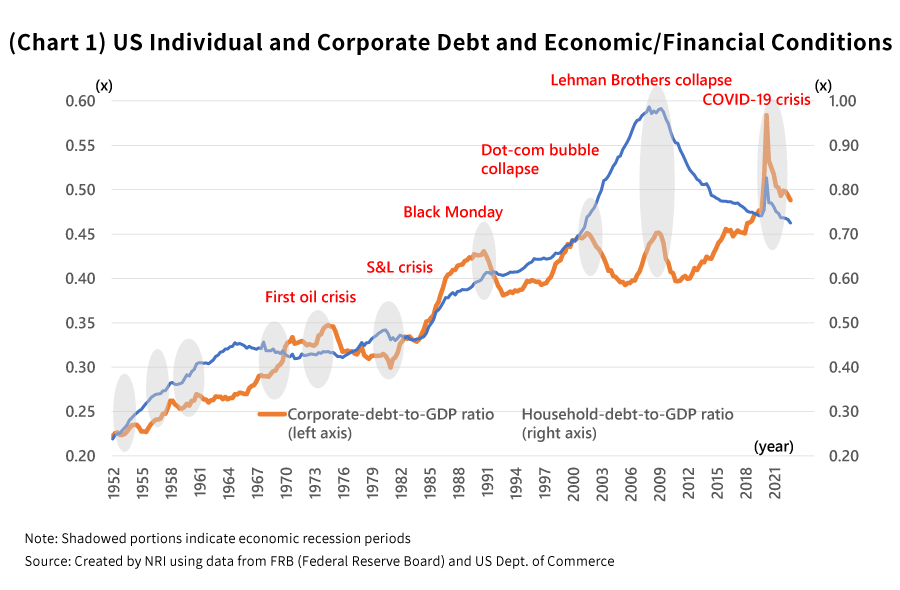

Before the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008 (the global financial crisis), the ballooning of individual debt and the skyrocketing of housing prices had been proceeding simultaneously. Yet subsequently, there came a so-called deleveraging (debt reduction) period, and the proportion of GDP made up by individual debt rapidly began to fall (Chart 1).

The curtailing of debt led the burden of interest payments to cease rising as they had been, as a result of which the economic activity of individuals seemingly created more resistance to interest rate hikes. For this reason, financial problems involving individual debt in the form of housing loans, residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), automobile loans, and so forth also have not grown very severe so far.

Corporate debt hits historically high levels

As opposed to this trend in individual debt, US corporate debt spiked in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Whereas its ratio to GDP had stayed more or less unchanged since the 1980s, it suddenly began to rise starting in 2011, and over the past several years it has reached historically high levels. This is likely attributable to the substantial decline in financing costs in response to rapid monetary easing.

It would seem that the growth of corporate debt has made corporate economic activity more susceptible to interest rate hikes than before. The weakness in capital investments has recently become quite pronounced, a sure sign of the effects of rising interest rates.

Financial crises always appear in different forms at different times

With the debt environment having changed in this way, the risks to economic activity posed by rising interest rates have shifted from the private sector to the corporate sector. The same is likely true of risks on the financial front as well.

If we look back at past economic and financial crises in the US, we see that these occurrences have reflected the changing debt situations for individuals and corporations. The 1980s S&L (savings and loan) crisis occurred against the backdrop of increasingly high corporate debt, while 1987’s Black Monday crash was precipitated by excessive levels of capital investment by individuals accompanied by the growth in personal debt. The dot-com bubble collapse in 2000 had to do once again with rising corporate debt, whereas the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008 was triggered by rising personal debt involving the housing sector.

The alternating occurrence of economic and financial crises rooted in the growth of personal debt and those rooted in rising corporate debt is characteristic of the US. Rather than repeatedly showing up in the same form, financial crises always appear in different forms at different times.

Will the deterioration of economic conditions and corporate management fuel further banking woes?

Given the above, it would seem that the effects of this monetary tightening in the US this time are likely to show up first in corporate economic activity, and then in turn to grow into financial problems involving corporate debt.

On May 1, 2023, US regional bank First Republic Bank went bankrupt. This gave the impression that the banking troubles that began with the bankruptcies of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in March are not yet over.

At the bottom of these banking business concerns is a failure of interest rate risk management. The growth of unrealized bond losses following rapid interest rate hikes, as well as the decline in valuations of fixed-rate loans, lie at the core of the problem. Faced with a run on deposits, the banks were forced to sell off their assets, leading their unrealized losses to become realized losses, which created a strong headwind for their management.

On the other hand, we have yet to see a conspicuous rise in credit risks materialize following this rash of corporate management woes. However, if the effects of monetary tightening or constrained bank lending do lead corporate management to deteriorate further, that could degrade the quality of loans made to corporations, leading banks to face new adversities and nonperforming loan problems.

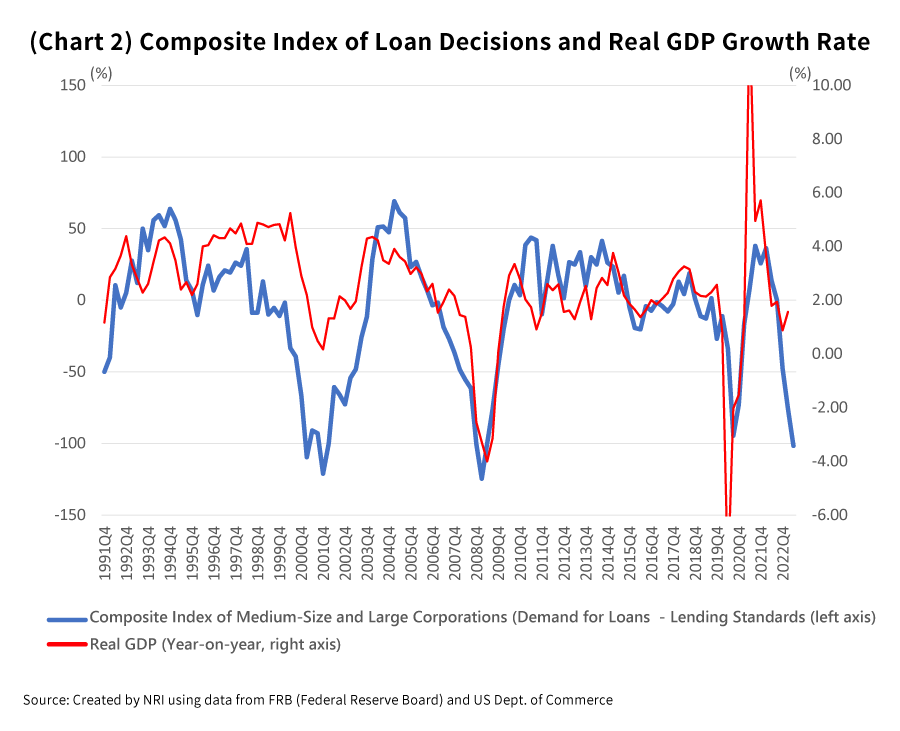

According to a bank lending survey released in May by the FRB (Federal Reserve Board), it was found that bank lending standards are becoming more stringent, and that corporate credit demand has also gotten more serious. If we create a composite index reflecting the effects of both the supply and demand aspects of this financing, the results suggest that business lending conditions have worsened to about the same level seen at the time of the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, the financial crisis in 2008, and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, and there is a considerable risk that the US economy could enter a full-fledged recession going forward (Chart 2).

Indicator of note shifts from deposit outflows to stock price drops

The outflow of deposits at midsize banks that gained attention in March abruptly pushed banks from a liquidity crisis to bankruptcy. Yet recently, this large-scale deposit outflow trend has been abating. We are starting to see that the movement of large deposits of $250,000 or more not covered by deposit insurance from banks with questionable management to other banks is running its course.

However, these banking management insecurities—in response to the growth of unrealized losses and deteriorating net interest income attributable to a yield curve inversion—are still ongoing. As in the example of First Republic Bank, those banks will likely find themselves subject to bailout takeovers in the form of intervention by the financial authorities.

It would seem that banks contemplating takeovers of other banks are becoming more inclined to go through with them after waiting for the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) to embark on bankruptcy procedures, which involve taking over the day-to-day operations of the failed bank. This is because if these bankruptcy procedures are implemented, the FDIC will carry a portion of that bank’s losses using the deposit insurance fund.

Further, if expectations over bankruptcy procedures and takeovers of financially troubled banks intensify, the market will quickly begin to reflect the unrealized losses of bonds and loan assets in the banks’ corporate value. This is because if the banks survive their unrealized losses will not materialize, but if they undergo bankruptcy procedures or are taken over, then they will be subjected to strict asset assessments and mark-to-market valuations. For this reason, if expectations of bankruptcies or takeovers mount, they can easily lead the stock prices of financially troubled banks to tumble.

Until now, bank deposit outflows have been a key indicator in the search for the next potential failed bank, but perhaps falling stock prices will merit closer attention going forward.

Major risks to liquidity channels for companies with low credit ratings

If corporate activity deteriorates and management falters going forward, that could easily give rise to financial problems in the channels used to provide liquidity to companies. That would mean a drop in the quality of corporate loans being made by banks, a decline in the prices of securities having to do with corporate debt, and so forth, and could turn into a management problem both for banks and for funds and other non-bank entities (non-bank financial intermediaries).

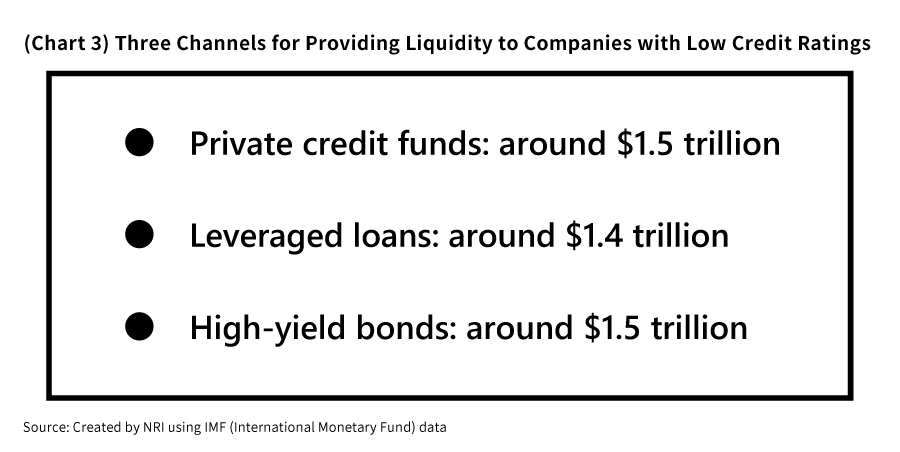

In particular, there would seem to be three channels for supplying funds to companies with low credit ratings—namely private credit funds, leveraged loans (bank loans to firms with low credit ratings), and high-yield bonds (speculative-grade bonds)—could become an epicenter of financial instability. Those three channels are roughly shoulder-to-shoulder in terms of asset scale at around $1.5 trillion, $1.4 trillion, and $1.5 trillion in size, respectively (Chart 3).

In addition, if poor management of companies with low credit ratings also leads to a major price drop for CLOs (mortgage-back securities), a type of leveraged loan securitized product, then open funds—which invest in those CLOs and high-yield bonds and which can be terminated at any time—could also see withdrawals of large volumes of client funds and find themselves in risk of collapse. Open investment funds are now contending with a “liquidity mismatch” problem whereby the funds they accumulate are highly liquid but the investment targets have low liquidity, and this could also ultimately mean higher risks of financial market disruptions.

The weaknesses of the US economic and financial system, their Achilles’ Heel, lies in corporate sectors which excessively inflated debt. It’s even conceivable that a new type of financial instability, one weaving together banks, financial products, and funds, could arise going forward in conjunction with deteriorating economic conditions and corporate management.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.