Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Parsing the Bank of Japan Literature for the Future Course of a Monetary Policy at a Crossroads

It has been three months since Kazuo Ueda became Governor of the Bank of Japan back in April. At first, some were of the view that as the new Governor, Mr. Ueda would set out to revise Japan’s extraordinary decade-long monetary easing policy as soon as he took office, but in fact, he has now put off any such policy revisions at two Monetary Policy Meetings since taking the helm. Trying to predict what monetary policy will be going forward will require the work of carefully parsing the messages the BOJ sends, known as the “BOJ literature” due to their complex and difficult-to-understand nature.

Have expectations of policy revisions diminished too greatly?

When the BOJ decided last December to expand the variability range of its Yield Curve Control (YCC), it reinforced the view in the financial markets that starting in April of this year, monetary policy would be revised rapidly under the new governor.

In actuality, however, Governor Ueda has repeatedly stressed his intention to continue with this unprecedented monetary easing. For that reason, expectations in the financial markets about policy revisions have diminished, and in some sense, that has helped further the weakening yen and higher stock price trends seen since the beginning of the year.

When two-year JGB yields briefly moved to positive territory, the markets factored in the possibility that negative interest rates could be eliminated soon, but now even three-year JGB yields have reverted to negative levels, leading the markets to adopt the view that the negative interest rate policy is not going anywhere for the moment. Some are now even of the opinion that we may not see the end of negative interest rates or any other full-scale policy revisions happen at all during Governor Ueda’s five-year term.

However, the reality is that this revised view in the financial markets may be an overstep. Given that Governor Ueda has pointed out numerous side effects of this extraordinary monetary easing program, he can be expected to make reasonable progress in changing BOJ policy during his five-year term.

Parsing esoteric “BOJ Literature”

Governor Ueda has emphasized he will strive to provide information in an “easy-to-understand manner”, but the terminology used by the BOJ is generally regarded as difficult to understand, and its communications have even come to be referred to as the “BOJ Literature”.

Although Governor Ueda has repeatedly stated that “it is appropriate for the Bank of Japan to continue monetary easing”, I believe this phrasing has in a way created a misapprehension in the market that he intends for this unprecedented monetary easing to be maintained unchanged going forward.

The continuation of monetary easing in this context does not mean making no policy revisions of any kind (e.g., raising interest rates), but rather likely means staying the course on monetary easing. For example, even if the BOJ were to enact a policy revision that entailed raising short-term policy interest rates from their current -0.1% to 0% and thereby eliminating its negative interest rate policy, interest rates would still be kept at historically very low levels, and the easy money status quo would persist.

Even if the 2% inflation target insisted on by Governor Ueda cannot be achieved anytime soon, and the BOJ is consequently forced to prolong its monetary easing program, it will likely go through with necessary policy revisions.

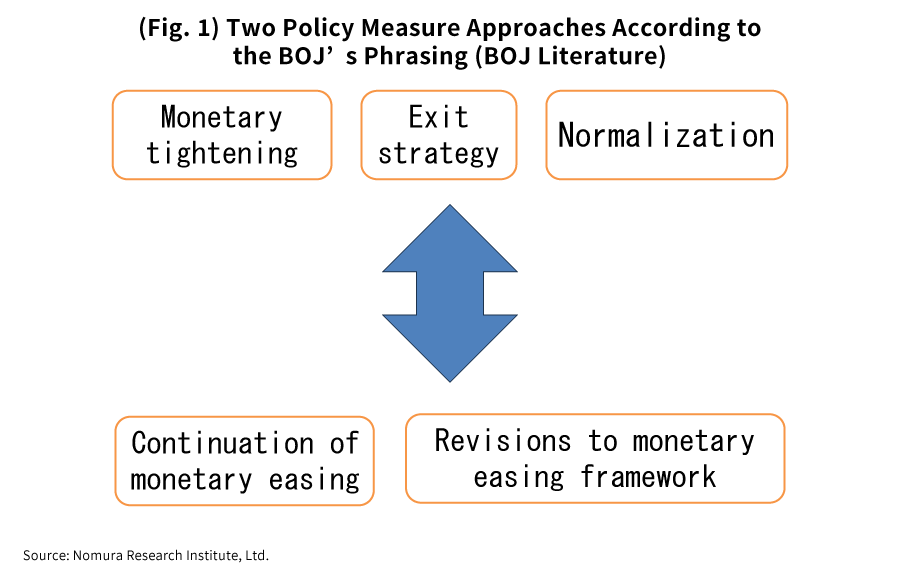

Now, if we try to parse the “BOJ Literature” put out under Governor Ueda’s tenure, we see that when it comes to monetary policy measures in a scenario where the 2% inflation target has been achieved, Governor Ueda uses terms such as “monetary tightening”, “exit strategy”, and “normalization”, whereas the policy measures that would be necessary if the BOJ judged this target not to be swiftly achievable are referred to as “revisions to the monetary easing framework”, and it seems that he clearly distinguishes these two categories (Fig. 1).

If the BOJ did determine its 2% inflation target to be unachievable anytime soon, then the prolonging of its monetary easing policy would be inevitable. But in order to get through the long haul, the BOJ could be expected to go ahead with revising its monetary easing framework, in the name of mitigating any side effects that could interfere with the continuation of that easing.

BOJ at a crossroads about its inflation target

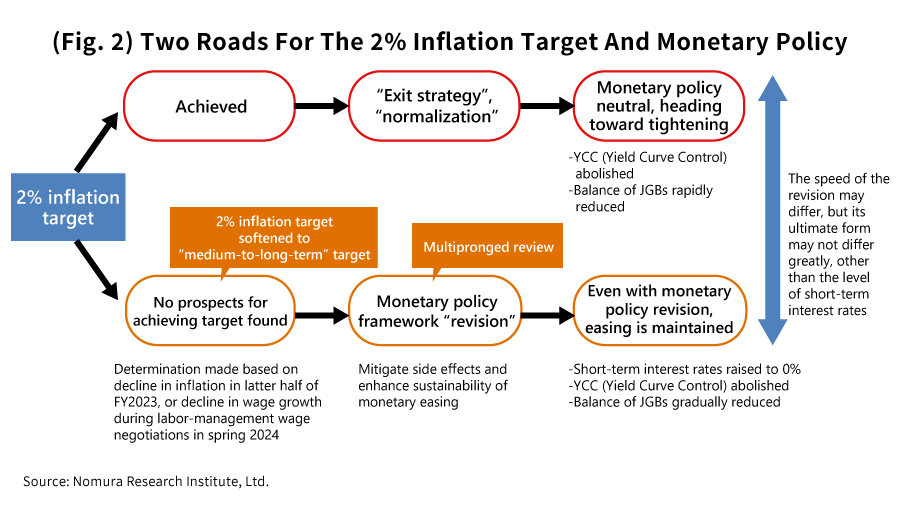

The BOJ is currently standing at a crossroads with regard to its 2% inflation target. One could say that there are two roads stretching out before it.

With the first road, if the pace of wage growth rises even further next year, with sustained price increases accompanying this wage growth, the BOJ would interpret this as a sign that the achievement of its 2% inflation target is in sight (Fig. 2). In this scenario, the BOJ would make a clear shift in its monetary policy, and would head in the direction of “monetary tightening”, “exit strategy”, and “normalization”, as often cited by Governor Ueda.

On the other hand, if instead we see the inflation rate decline as the effect of falling crude oil prices or the depreciation of the yen dissipates, and this leads the pace of wage growth to slow down in next year’s labor-management wage negotiations, thus dimming any prospects for swiftly achieving the 2% inflation target, the BOJ could be expected to soften its stance and rebrand its 2% target as a “medium-to-long-term” goal. This is the second road.

Governor Ueda has repeatedly said that achieving the 2% inflation target will not be easy, and we may assume that the Governor himself may believe that the BOJ is likely to head down that second road.

What we must note is that no matter which of these roads the BOJ follows, the ultimate form of its policy revision is not likely to be all that different. The major differences will probably only involve the speed of the revisions and the level that short-term interest rates ultimately reach. Even with the second road, the bank’s negative interest rate policy and YCC will both presumably be abolished.

Will it all be decided based on next year’s spring labor-management wage negotiations?

As for whether the BOJ will deem its 2% inflation target achievable, or will instead judge that goal to be too difficult and soften it into a medium-to-long-term goal, perhaps the BOJ’s determination will be most heavily swayed by next year’s spring labor-management wage negotiations.

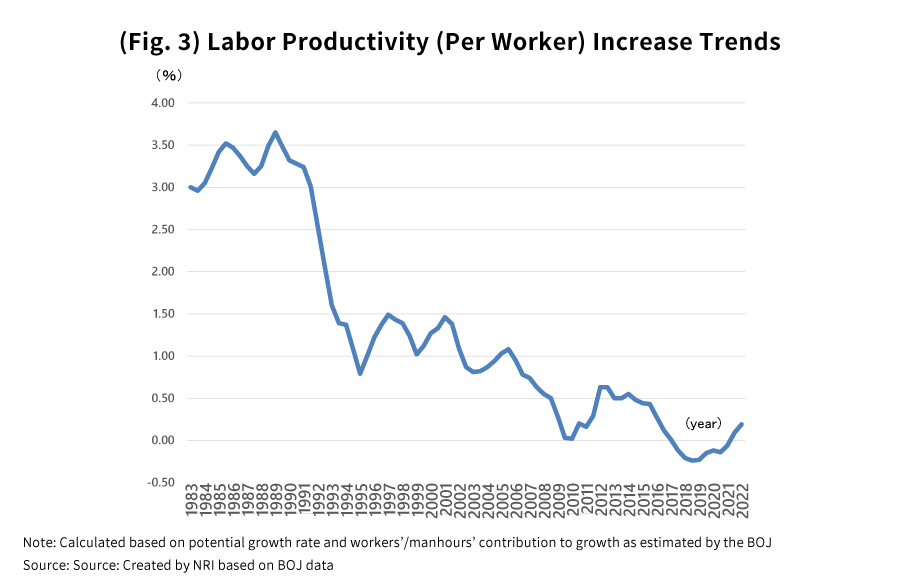

Former Governor Kuroda previously explained that in order to achieve the BOJ’s 2% inflation target, nominal wages (base wages) would have to rise by 3%. Absent any changes in the distributions, the labor productivity growth rate equals the real wage growth rate. Given also that the real wage growth rate equals the growth rate in nominal wages minus the expected inflation rate, according to my calculations, stably achieving a 2% inflation rate would require conditions in which the labor productivity growth rate is at 1%, and the growth rate in nominal wages (base wages) at 3%.

However, in actuality, at the beginning of the 1990s when prices were hovering stably at around 2%, the labor productivity growth rate was around 3% (Fig. 3). According to these figures, achieving the 2% inflation target would require the real wage growth rate to be 3%, and the nominal wage growth rate (base wages) to be as high as 5%. At present, with the labor productivity growth rate having dropped to near 0%, the 2% inflation target would seem to be scarcely achievable.

In fact, there appears to be a strong chance that, as a reflection of the decline in inflation, base wages could be in the range of 1% at next spring’s labor-management wage negotiations, which (although fairly high in the context of recent years) would be lower than the 2%-plus level seen this year.

Under these circumstances, I anticipate that once the BOJ has seen a drop-off in the wage growth rate during next spring’s labor-management wage negotiations, it will downgrade its future inflation forecast in next April’s Outlook Report, and will soften its 2% inflation target into a medium-to-long-term goal, thus embarking down that second road.

Yet even in that scenario, revisions to the monetary easing framework such as the elimination of negative interest rates and the abolition of YCC are not likely to begin immediately. Blocked by numerous obstacles including deteriorating economic conditions at home and abroad, growing speculation about monetary easing in the U.S., and the yen’s appreciation in the exchange markets, the BOJ may well not undertake a full-scale revision of its monetary easing framework until at least the latter half of next year or later.

That said, we must note the possibility that a YCC correction in the form of a further expansion of the bond yield variability range could be made separately sometime this year. As that was already done last December under former Governor Kuroda, who held a negative view toward policy revisions, any hurdles in the way of a similar move would seem to be low. The BOJ could even do that before the end of the year under the guise of a “softening measure”, as an extension of the revision made last December, rather than a full-scale correction of its monetary easing framework.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.