Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The BOJ’s Policy Revisions and Prospects for Soaring Prices

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) decided at its Monetary Policy Committee meeting on July 28 to take measures to loosen its Yield Curve Control (YCC) program targeting long-term JGB yields. This marks the first policy review by the Bank of Japan since Governor Ueda took office in April of this year. While there had already been speculation in the financial markets that measures would be taken to soften YCC sooner or later, the timing of this move has been received with some degree of surprise.

Taking the initiative, the Bank of Japan opts to conduct YCC with greater flexibility

Although the Bank of Japan has set a target range of around plus or minus 0.5% for 10-year government bond yields to fluctuate around zero as the target, with this latest decision, it has amended its language to rephrase this plus or minus 0.5% variability as a “reference” rather than as “rigid limits”, softening its stance with this added new phrasing. This means that going forward, the Bank of Japan will allow 10-year government bond yields to exceed the former cap of plus 0.5%.

Up to now, the Bank of Japan has never permitted 10-year JGB yields to go above the upper limit of its variability range. For that reason, with yields currently approaching that upper limit, the Bank of Japan was compelled to make massive purchases of government bonds to curb any further yield increases, through extraordinary JGB purchase operations and fixed-rate purchase operations. That will ultimately enhance certain side effects, namely by expanding the bank’s balance sheet, reducing the functionality of the government bond market, and intensifying the current de-facto tendency of government financing. Those effects are the major price that’s being paid to maintain the YCC framework.

Last year, at the time that the rise in long-term U.S. government bond yields pushed up long-term JGB yields in Japan, the Bank of Japan responded by forcibly checking those yield increases, which led the interest rate differential between the U.S. and Japan to grow and caused the yen to depreciate dramatically. A depreciating yen will only exacerbate the current price surges by leading to higher import prices. There has also been mounting criticism from the public regarding the Bank of Japan’s policy stance for its lack of flexibility. It’s conceivable that this further softening of policy—following the Bank of Japan’s move last December to expand the YCC variability range—was also meant to address such criticism.

The Bank of Japan isn’t being driven to enact these softening measures because 10-year JGB yields are approaching the upper limit of the variability range. Rather, it’s taken the initiative by deliberately timing this move at a moment when the financial markets are still stable.

A yield rise of 1.0% will not be tolerated at the moment

The Bank of Japan has now decided to purchase an unlimited quantity of 10-year JGBs through fixed-rate operations each business day at a new set yield of 1.0%, instead of at its former upper limit of 0.5%. For that reason, the yield variability cap is now said to have effectively been raised to 1.0%.

Yet in fact, the Bank of Japan does not intend at present to permit yields to rise that far. Governor Ueda has even explained that these fixed-rate operations each business day at the 1.0% cap is simply a “preemptive measure”.

While it’s willing to conduct its fixed-rate operations every business day at the 1.0% rate indefinitely, the Bank of Japan has also stated that it will be “making nimble responses through, for example, increasing the amount of JGB purchases and conducting fixed-rate purchase operations for nonconsecutive days and the Funds-Supplying Operations against Pooled Collateral”. By using these means, the Bank of Japan will be able to contain the rise in yields.

Yet I believe the Bank of Japan will manage to avoid explicitly stating the de-facto upper limit that it’s prepared to tolerate. That’s because such a statement would be contrary to the purpose of softening its policy, which is to leave the yield variability to the market’s discretion to some extent. As for the degree to which the bank will permit yields to rise, that will also depend on the economic and price conditions going forward.

An explicit upper limit would also give the markets a target, and potentially could intensify market disruptions. However, in terms of a rough reference point for the bank’s tolerance toward yield rises at the moment, the Bank of Japan might possibly be envisioning a cap of around 0.75%, in the middle of the range between 0.5% and 1.0%.

Meanwhile, as long as it doesn’t become the new normal for 10-year JGB yields to rise to 1.0%, the Bank of Japan likely won’t seek to implement any further such tweaks to YCC.

Given that the current round of softening measures will permit only a limited increase in yields, there would seem to be little likelihood that we’ll see developments like yen appreciation and falling stock prices accelerate and cause turbulence in the financial markets, or that any conspicuous adverse effects will arise for economic or price conditions.

The BOJ indicating its view that inflation above 2% won’t last

Last December when the Bank of Japan chose to expand the YCC variability range, that decision led to significant turmoil in the financial markets. That was because the markets interpreted the bank’s move as laying the groundwork for full-scale policy revisions to be undertaken right away under the new Governor’s administration beginning this April. Various media outlets also simultaneously reported this development as a “de-facto rate hike”.

This time, however, it seems that the bank has managed to skillfully implement these softening measures while mitigating their impact on the financial markets. That’s probably because the Bank of Japan had already instilled in the financial markets the understanding that softening measures would be clearly distinct from a full-scale policy revision.

The Bank of Japan has stated that achieving its 2% price stability target is a prerequisite for policy normalization. Under these circumstances, it has repeatedly conveyed that achieving 2% stable inflation is currently “not in sight”, in light of which the markets have understood that these new measures will not be a prelude to policy normalization, or to a full-blown policy revision.

Also notable at the Monetary Policy Committee meeting held on July 28 was the price forecast in the “Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices (Outlook Report)”. FY2023 consumer prices (excluding fresh foods) showed a year-on-year rise of 2.5%, a significant upward revision from the 1.8% rise stated in the previous report made in April.

Governor Ueda has therefore explained that the emergence of an upside risk in the price outlook was one reason that the bank chose to implement softening measures at this time. If the inflation rate were to climb and to be accompanied by a rise in the markets’ medium- and long-term inflation expectations, that could put increased upward pressure on 10-year JGB yields, and thus in some sense the bank made a pre-emptive move to create some leeway for yields to rise.

On the other hand, the FY2024 price outlook stood at plus 1.9%, which was instead a downward revision from the 2.0% rise stated in the previous report. And the FY2025 outlook was even lower at just plus 1.6%, unchanged from the last report’s outlook.

This signifies that the Bank of Japan has become confident in its outlook that the current inflation rate of more than 2% will not be sustained, and that it will again fall below 2% sometime during the bank’s forecast period. I believe that by indicating this to the public, the Bank of Japan may also have intended to quell market speculations that the current round of softening measures will lead soon to a full-fledged policy revision.

Medium- and long-term inflation expectations differ from country to country

Incidentally, the crisis posed by global price surges finally appears to be ending. The year-on-year rate of increase in the June CPI in the U.S. was 3.0%, reflecting 12 straight months of decline, and hitting the lowest level seen in two years and three months. This is already just one-third the rate of increase that was seen back during peak inflation. In the Eurozone as well, the year-on-year rate of increase in consumer prices fell to around half of what it had been during peak times.

As soaring prices overall continue to come down from their peaks across the world, there have been also growing variations among different countries. Viewing this by major country, we see that the inflation rate in the U.S. fell ahead of the rate in other countries, with the rate in the Eurozone subsequently following its lead, whereas in Japan, the peaking-out of the inflation rate has yet to be quite so apparent. Conversely, prices in China have been on the decline.

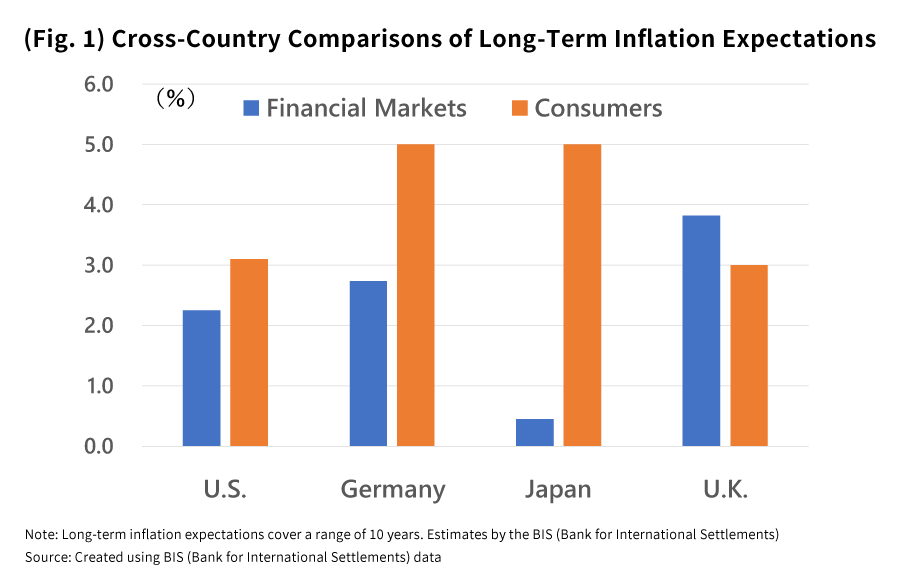

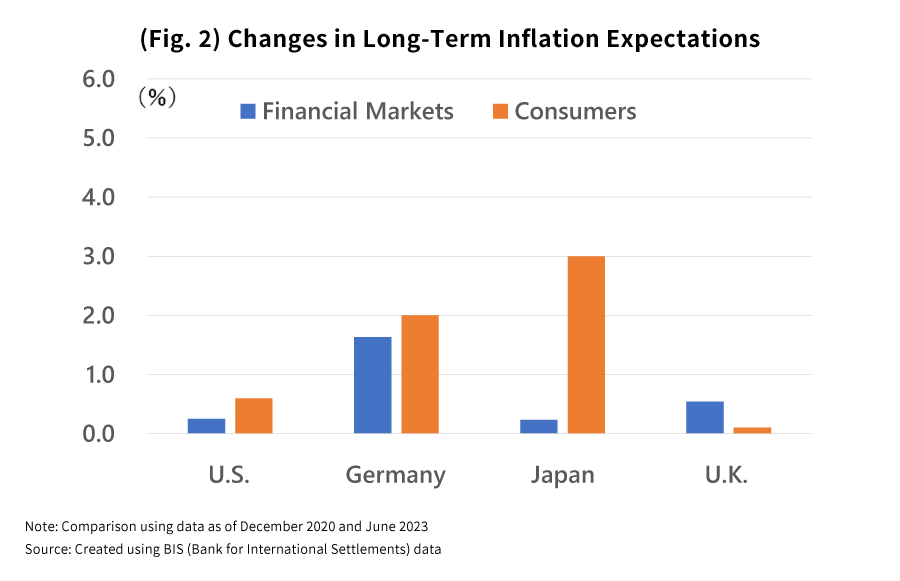

I think what’s been contributing to these variations in inflation rates among countries are the changes in long-term inflation expectations. According to calculations by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 10-year inflation expectations in the U.S. have recently been a little over plus 2% in the financial markets, and slightly more than plus 3% among consumers, meaning that there has been little increase compared to the end of 2020 just before prices began to surge (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Although the CPI inflation rate in the U.S. briefly rose to nearly 10% year-on-year, long-term inflation expectations have nevertheless remained stable, a fact that I believe can be attributed to the substantial rate hikes enacted by the Federal Reserve Board (FRB). Given that long-term inflation expectations have held steady, we may suppose that the inflation rate going forward is likely to converge relatively quickly to that level.

Long-term inflation rate in Japan sees an uptick

It’s worth noting that in contrast to the situation in the U.S., long-term inflation expectations among Japanese consumers have been trending significantly upward. According to BIS estimates, they have gone up by three percentage points since the end of 2020 and have even risen five percentage points in recent months. Unlike the central banks in Europe and the U.S., the Bank of Japan—with its insistence on the 2% price stability target—has opted not to revise its monetary policy even amid rising inflation and has been tolerant of upward deviations in long-term inflation expectations, and its stance has probably contributed greatly to this uptick. Given the foregoing, while the inflation rate in Western countries might come down relatively rapidly going forward, in the case of Japan there’s a risk that inflation could take longer to fall.

Although some may hold the view that substantial rises in long-term inflation expectations are desirable for achieving the 2% price stability target, I believe that thinking may be dangerous. The recent major upswing in the inflation rate and significant rise in long-term inflation expectations, which are dissociated from the actual strength of the Japanese economy, could compromise Japan’s economic stability.

For instance, since corporate long-term inflation expectations likely haven’t risen as much as expectations among everyday individuals have, companies might continue to be cautious about raising wages significantly, and consequently the wage growth rate won’t keep up with the high long-term inflation expectations among consumers. If that does happen, there’s a risk that individual consumers may suddenly decide to curb their spending.

Going beyond tweaking YCC for greater flexibility to full-scale policy revisions

The Bank of Japan has repeatedly commented that there is still a long way to go to achieve a sustainable and secure 2% price stability target along with wage growth. They’re right about this, but while the recent rise in the inflation rate may be just a temporary uptick, achieving the 2% price stability target in the short term appears to be difficult.

However, I believe this 2% price stability target that the Bank of Japan was forced to adopt 10 years ago under political pressure was never appropriate in the first place. The fact remains that this target is too high given the actual potential of the Japanese economy.

Instead of holding fast to its 2% price stability target, the Bank of Japan ought to take a stronger posture to ensure medium- and long-term price stability to stabilize the Japanese economy and people’s livelihoods. As one part of that, perhaps it should go beyond these most recent tweaks to enhance YCC’s flexibility, and promptly implement genuine policy revisions such as eliminating negative interest rates.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.