Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Attention Gathering on Next Spring’s Labor-Management Wage Negotiations and the BOJ’s Price Stability Target

Speculation is mounting in the financial market that the Bank of Japan will move to eliminate its negative interest rate policy next April, embarking on a full-scale revision to the extraordinary monetary easing that has been in place for over 10 years. The expectation is that once the results of the spring labor-management wage negotiations confirm substantial wage hikes among leading companies in mid-March next year, the Bank of Japan will declare its 2% price stability target achieved and then undertake fully-fledged policy revisions. However, the situation remains quite fluid.

Labor unions to seek more robust wage hikes in next spring’s labor-management wage negotiations

According to Rengo, Japan’s largest labor union, the actual wage increase from this year’s negotiations was +3.6% for wages as a whole, and the base pay increase not including the regular annual wage hike was just over +2%, the highest level seen in 30 years.

However, the September real wage growth rate (nominal wage growth rate – inflation rate) was -2.4% year-on-year, making for 18 consecutive months of decline, and with the inflation rate continuing to outpace the wage growth rate, people are still feeling the squeeze in their everyday lives.

That being the case, the government and labor unions are looking to create conditions that will enable the wage growth rate to overtake inflation as soon as possible. On October 19, Rengo announced the “Basic Concept” of its approach to the spring 2024 labor-management wage negotiations. It raised its overall wage hike target from “around 5%” as stated in 2023 to “5% or more” for 2024, and raised its base pay hike target from “around 3%” to “3% or more”.

With these targets having been raised further, there are also mounting expectations that next year’s wage hike rate will significantly eclipse this year’s. In fact, if economic conditions remain stable and labor market conditions continue to be tight, then during next spring’s negotiations the wage growth rate could even reach its highest level in recent years.

A drop in the inflation rate could present trouble

However, it remains to be seen whether next year’s wage growth rate will significantly surpass this year’s rate. That’s because a downward trend in the inflation rate would be an adverse factor for wage growth.

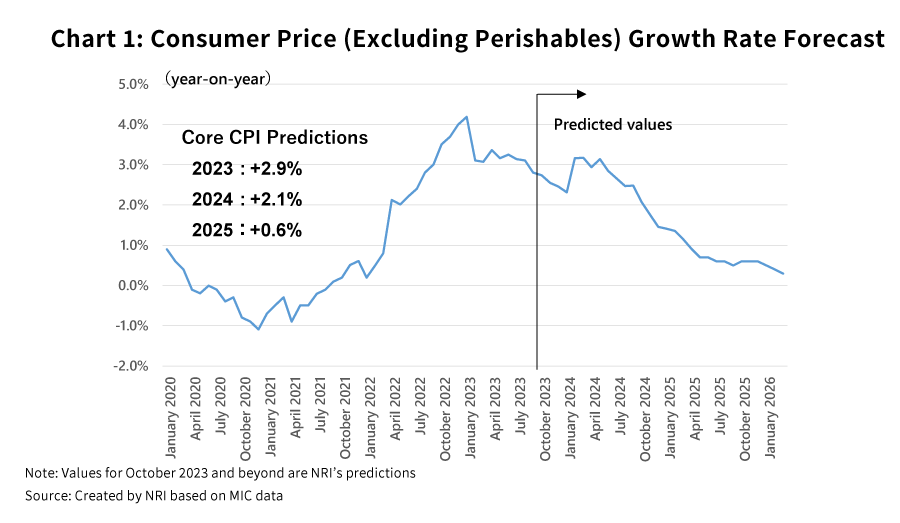

In the January Consumer Price Index, which was used as a reference when this year’s wage negotiations were coming to a head, the Core CPI (excluding perishables) growth rate was at +4.2% on the year. By contrast, the current Core CPI was 2.8% higher year-on-year in September, falling below 3% growth for the first time in 13 months. Furthermore, this figure is projected to drop down to just over 2% growth next January. That would only be at around half the level seen this past January (Chart 1).

Given the history involved here, in which price trends have played a major role in Japan’s wage decisions, it’s possible that under such price conditions the wage growth rate next year won’t necessarily outpace this year’s level by very much. One thing that does have a major effect on prices by way of higher private consumption and corporate labor costs is base pay growth, but that can be expected to increase by around +2.5% next year at the most.

In the latest Short-Term Economic Survey of Enterprises (Tankan) from September released by the Bank of Japan, the average forecast for inflation five years down the road among companies surveyed (All Enterprises and Industries) was +2.1%. Being that the medium-term inflation forecast was around +2.0%, companies are presumably reluctant to raise their base pay by a level far more than that. Given how difficult it would be in Japan to negatively adjust base wages and reduce people’s base salaries, companies will likely be careful when deciding their yearly base wage increases, mindful of the risk that future labor cost increases could put pressure on their earnings.

As a result, it’s expected that positive growth in real wages will not come next year but will rather be pushed off till 2025.

Would a base pay increase consistent with the achievement of the 2% price stability target be between +4% and +5%?

The prevailing view in the financial market now is that in response to the substantial wage growth rate coming from next spring’s labor-management wage negotiations, the Bank of Japan will judge its 2% price stability target to have been achieved, and then embark on a full-scale revision of its monetary policy. In concrete terms, many expect that at the Monetary Policy Meeting to be held next April, the Bank will decide to do away with negative interest rates.

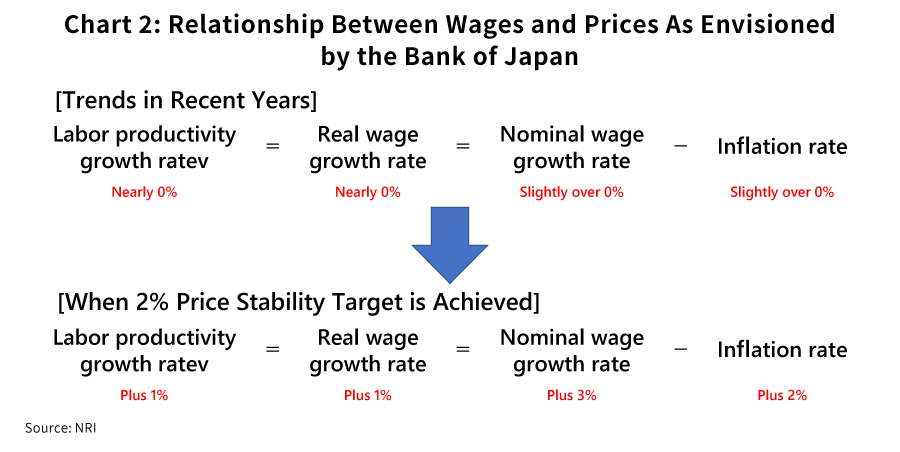

Yet it’s not clear how high the wage growth rate specifically needs to be for the Bank of Japan to judge that its price stability target has been achieved. Incidentally, former BOJ Governor Kuroda previously remarked that a base pay increase of around +3% would be consistent with the achievement of the 2% price stability target.

However, with the inflation rate falling, there would seem to be little chance that the base pay increase to come out of next spring’s negotiations will surpass this year’s rise of slightly over 2% to reach roughly +3% (Chart 2).

In actuality, the hurdle for raising base pay to achieve the 2% price stability target might be higher than that.

The CPI inflation rate trend was previously at around +2% at the beginning of the 1990s, but at that time the growth rate in scheduled wages corresponding to base salaries was +4.4% in 1991. In addition, if calculated based on the labor productivity growth rate and the corresponding real wage growth rate, then a base pay increase commensurate with a roughly +2% CPI inflation rate trend would work out to +5.5%.

Only once the trend in base pay increases reaches this high level would the inflation rate also stably and sustainably hit about +2%, which would seem to come close to achieving the price stability target being touted by the Bank of Japan.

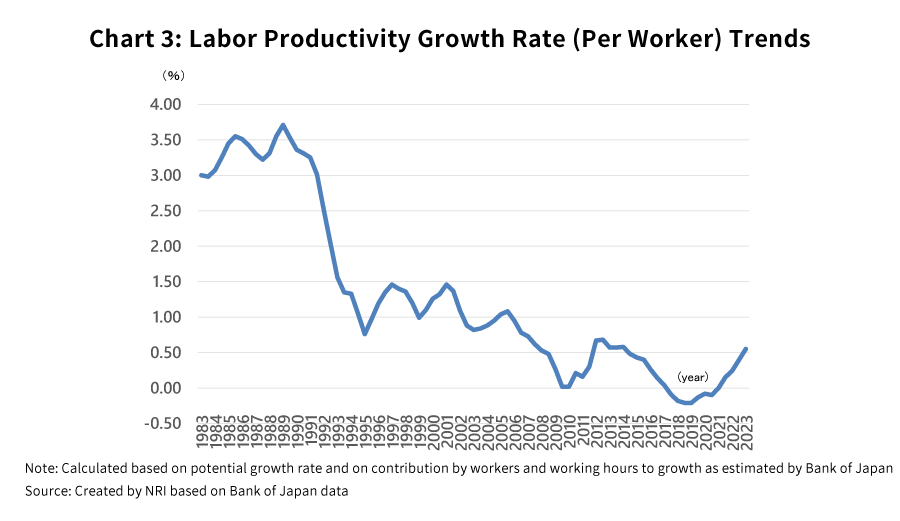

However, there’s a major difference between then and now in terms of economic potential, namely when it comes to the labor productivity growth rate which determines trends in the wage growth rate and the inflation rate. At that time the potential growth rate was in the +4% range, while the labor productivity growth rate—which determines the real wage growth rate—was at about +3.5%. Yet currently, each of those figures is at most in the +0.5% range (Chart 3). With economic potential being what it is, it would appear rather difficult for the inflation rate to trend stably and sustainably at around +2%.

Bank of Japan won’t decide on a major policy shift based solely on the outcome of the spring labor-management wage negotiations

If we consider the adverse factors at play such as the drop in the inflation rate, it’s essentially unthinkable that the base pay increase coming out of next spring’s labor-management wage negotiations will suddenly jump from the slightly over +2% rate seen this year to the range of +4% to +5%. Given this, it seems unreasonable to suppose that following the results of the wage hikes from next year’s negotiations, the Bank of Japan will immediately declare its 2% price stability target achieved and go through with a full-scale policy revision.

While the Bank of Japan is no doubt deeply focused on next spring’s negotiations, it’s worth pointing out that the wage growth rate is but one indicator the Bank will be using to determine whether the 2% price stability target has been achieved, and furthermore, it’s not typical for the Bank to decide on any major shifts in policy based on just one indicator.

On the other hand, given how significant the side effects of its current extraordinary monetary easing policy are, the Bank of Japan presumably is highly inclined to revise that policy regardless of how close it is to achieving its 2% price stability target.

I would venture that the wage hike to come during next spring’s negotiations won’t quite reach the level expected. The Bank of Japan might even decide considering the outcome of those negotiations that the achievement of its 2% price stability target is not yet in sight. Moreover, the Bank could be expected to announce that it will persist with its monetary easing policy.

Yet prolonging monetary easing would bring greater risks of various side effects, and if those risks were to materialize, they would likely impede the continuation of the monetary easing policy. Under the nominal aim of eliminating those side effects, the Bank of Japan in fact might gently pursue measures to mitigate side effects by making a de-facto policy revision while avoiding any disruptions to the financial market.

In actuality, I would wager that the Bank of Japan will wait until the latter half of 2024 or later to undertake a full-scale policy revision, starting with the elimination of its negative interest rate policy.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.