On March 19, 2024, the Bank of Japan rescinded the negative interest rate policy it had maintained for approximately eight years, and it raised interest rates for the first time in 17 years. While I would like to welcome this decision, I think it might have been better if the Bank of Japan had made this move earlier. Had it embarked on a policy correction several years ago when prices began skyrocketing worldwide, the yen likely wouldn’t have depreciated to the extent that it now has, and people’s inflation fears also probably wouldn’t have risen so high.

Bank of Japan ends the negative interest rate policy it introduced in 2016

There are three main points to note about this policy correction. The first is that it does away with

the negative interest rate policy. The Bank of Japan has now reset its “policy interest

rate”, shifting away from the rate applied to policy rate balances in current accounts held by

financial institutions at the Bank and back to what the uncollateralized overnight call rate target was

prior to the introduction of the negative interest rate policy in 2016, and has raised its level from

the existing range of -0.1% to 0% up to the range of 0% to 0.1%, which is an increase of 0.1%.

The second point is the abolition of YCC (Yield Curve Control) which sets targets for long-term interest

rates. Following the two rounds of softening measures implemented last year, YCC had already become

something of a mere formality. While the Bank officially decided to abolish YCC, it also opted to

continue purchasing long-term JGBs in the monthly amount of roughly six trillion yen, which would be

almost the same amount seen thus far. The aim of this is to prevent long-term interest rates from

fluctuating too significantly in response to the elimination of YCC. If long-term interest rates were to

rise dramatically, the Bank stated, it would flexibly increase the purchase amount or implement

fixed-rate purchase operations, funds-supplying operations against pooled collateral, and so forth. The

continuation of JGB purchases in this amount could be considered a transitional measure, just until the

Bank of Japan can commence “quantitative tightening (QT)” to reduce its outstanding balance

of JGBs and shrink its balance sheet.

The third point is that the Bank will stop purchasing ETFs (exchange traded funds) and other such

instruments. The Bank will no longer be making any new purchases of ETFs or of J-RIETs (real estate

investment trusts). In addition, it will gradually be drawing down the amounts of CP (commercial paper),

corporate bonds, and so on that it purchases, aiming to conclude all such purchases in one year’s

time. However, given that its ETF and J-RIET purchases have already nearly halted, this arguably does

nothing more than confirm the current status quo.

Prospects for policy normalization going forward

The Bank of Japan, stating that “large-scale monetary easing has fulfilled its role”, has

enthusiastically proclaimed its break away from its unprecedented monetary easing. However, this

decision can’t really be regarded as the major policy shift it might appear to be, and perhaps it

merely carries on much of the negative legacy of that unprecedented monetary easing, with its apparent

considerable side effects.

The scope of the policy interest rate hike is around 0.1%, just enough to bring the level back to the

range of 0%-0.1% from before the negative interest rate policy was rolled out in 2016. While the Bank

did decide to do away with YCC, the controlling of long-term interest rates will still be continued to

some degree. Further, long-term JGB purchases—that is to say, the quantitative easing policy

framework—will be maintained. Although new ETF purchases are no longer being made, the Bank has

yet to embark on full-scale normalization that would see it remove ETFs from its balance sheet.

The next key point is when the Bank of Japan will move to raise its policy interest rate further. At

present, I’m inclined to consider that the timing of that move could be pushed back to the

beginning of 2025. That’s because the rate cut expected to be made by the FRB (US Federal Reserve

Board) in the latter half of 2024 could very well significantly hinder the Bank of Japan from raising

its rates further. If Japanese and US monetary policy were to move in opposite directions

simultaneously, it could lead to major fluctuations in international capital flows, and rapidly weaken

the dollar while strengthening the yen, for example. Any weakness in domestic economic conditions might

also impede additional rate hikes.

However, if the wage hikes made at the spring labor-management wage negotiations are higher than

expected, and this increase appears to get passed on to consumer prices more than expected, or if the

yen continues to depreciate significantly, it’s possible that the BOJ may opt to raise interest

rates again in the fall and beyond. Furthermore, I’d suggest that it may raise its policy interest

rate up to 0.5% or even around 0.6% in the first half of 2025. I’d imagine that as being the peak

for the time being—that is, the terminal rate.

Subsequently, the target of the Bank of Japan’s policy corrections would likely shift from the

policy interest rate to balance sheet policy. The Bank of Japan may be foreseen in the latter part of

2025 to reduce the amount of long-term JGBs on its balance sheet, embarking on a so-called

“quantitative tightening (QT)”. Rather than selling its long-term JGBs in the market, it

would likely reinvest around half of the JGBs on its balance sheet that have reached maturity, thereby

gradually scaling down its outstanding JGB balance.

At that time, I believe, the Bank would probably set a new target for the pace at which it reduces that

JGB balance, opting to make minor adjustments in keeping with economic conditions and so forth. It could

well be a decade or even longer before the Bank reduces its outstanding amount of JGBs to normal levels,

and fully ends its quantitative easing policy.

Also a discrepancy between the Bank of Japan’s two explanations

Thus, the normalization of monetary policy has only just begun, and many difficulties likely lie ahead.

One of these is the confusion surrounding its communications with the market.

When the Bank of Japan rescinded its negative interest rate policy, it stated that “sustainably

and stably achieving our 2% price stability target is now in sight”. Meanwhile, given that

economic and price conditions remain weak, the Bank remarked that its policy interest rate won’t

be raised all that quickly, and that “accommodative financial conditions to prevail for the time

being”.

However, these two explanations seem in some sense to be rather at odds. If there’s a strong

chance that inflation will stabilize at 2% going forward, then keeping interest rates low would appear

unusual.

The Bank of Japan explained that “trend inflation is below 2%”, and that medium- to

long-term inflation expectations are also “still rising toward 2%”. Inflation expectations

are considered to be a leading indicator of the actual inflation rate, and the fact that even they

haven’t yet reached 2% likely means that the achievement of that 2% price stability target remains

uncertain.

Is the outlook just cherry picking?

Nevertheless, the Bank of Japan has now declared the achievement of its 2% price stability target in

sight, this being premised on the idea that if low interest rates persist for some time, they’ll

strongly bolster the economy, prices, and inflation expectations. Moreover, the Bank of Japan’s

price outlook is based on the inflation forecast in the financial market.

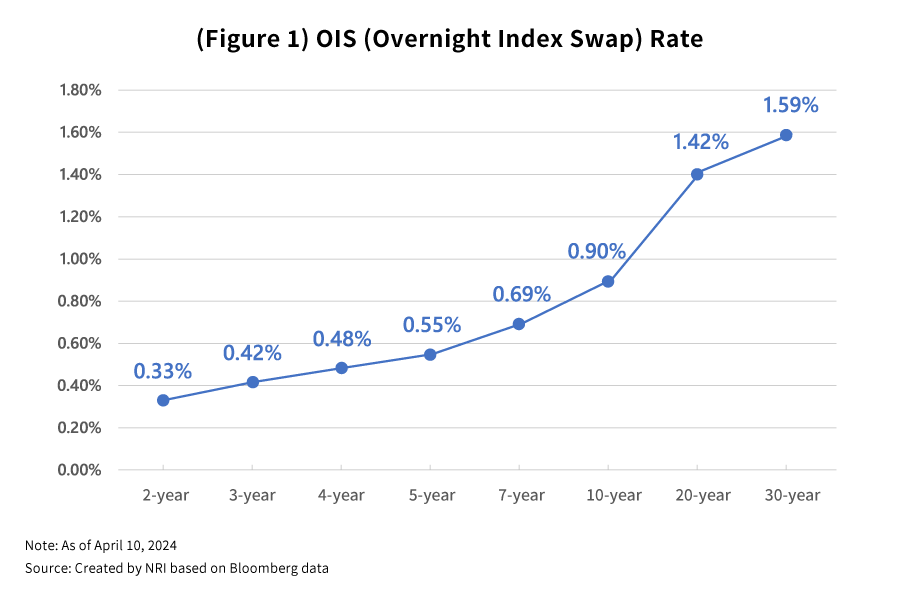

In the swap market, which reflects the future policy interest rate outlook, the two-year swap rate is at

around 0.3%, while underlying government bond yields are at around 0.2%. These rates reflect the

moderate interest rate increase outlook in the financial market that even if the policy interest rate

were to be raised further in the next year, it would only happen once at the very most.

Further, the fact that the 10-year swap rate is at around 0.9% might very well reflect the market

forecast that even in the medium- to long-term view, the 2% price stability target won’t be

achieved (Figure 1).

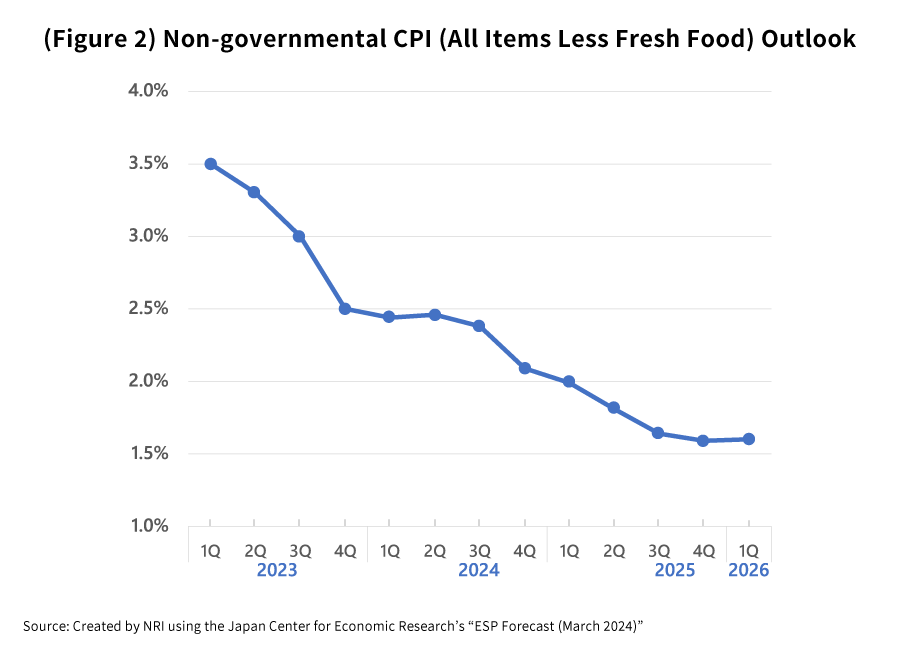

What’s worth noting here is that such market interest rate outlooks appear to be predicated on

rates being lower than the inflation forecasts given by the Bank of Japan. In the non-governmental CPI

inflation rate outlook, inflation looks to fall below +2% in early 2025, and then in the latter half of

that year to fall down to just the mid +1% range (Figure 2).

These two explanations by the Bank of Japan, which seem to be in conflict with each other, are based on

a sort of “cherry picking” approach, tying together the financial market’s interest

rate outlook with the Bank of Japan’s inflation forecast. This also creates the sense of a hidden

danger that may hinder the smooth normalization of monetary policy in the future.

Financial market also at risks of destabilization

It’s likely that the disparity between these two explanations from the Bank of Japan will

eventually begin to be bridged. The concern at that time would be that this could lead to confusion in

the financial market, and could also hinder the Bank of Japan from achieving a smooth policy

normalization.

Given that the Bank of Japan has officially declared the achievement of its 2% price stability target to

be in sight, if the financial market were to upwardly revised its own short-term interest rate forecast

accordingly, that might lead long-term interest rates to spike, and destabilize the financial market

through the appreciation of the yen, a drop in stock prices, and so forth. This is the short-term

risk.

Yet if we look at things from a longer perspective, over the next several years, for instance, there

would seem to be a strong possibility that the difference between the two outlooks could be bridged

while the inflation rate is trending below 2%. In that scenario, the Bank of Japan would face mounting

criticism that its declaration about achieving the 2% target was premature, and that in turn could also

impede the Bank as it tries to move forward with normalization.

Completely eliminating the so-called negative legacy of unprecedented easing will still require a great

deal of time. In that process, the Bank of Japan will be required to appropriately control the

expectations of the financial market while smoothly pursuing normalization, but that will be a highly

challenging policy.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.