Three triggers behind historic price surges

In many countries, the pace of inflation already seems to have peaked. However, with consumer prices holding at high levels, central banks are fearful that high prices could become firmly entrenched, and so they have continued with their monetary tightening policies. Could it be that after this bout of historic price surges, the world will have undergone a structural change from a low-inflation period to a high- inflation period? Assuming that is the case, then the era of low interest rates will also have come to a close.

What led up to the price surges we are seeing now were the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the policy responses made to those crises. But then there were three factors that directly triggered high inflation: the upward trend in the prices of oil and other commodities, supply constraints for manufactured goods stemming from supply chain disruptions, and the change in the structure of consumer demand from services to goods in response to infection risks. Yet all three of these triggers have already run their course.

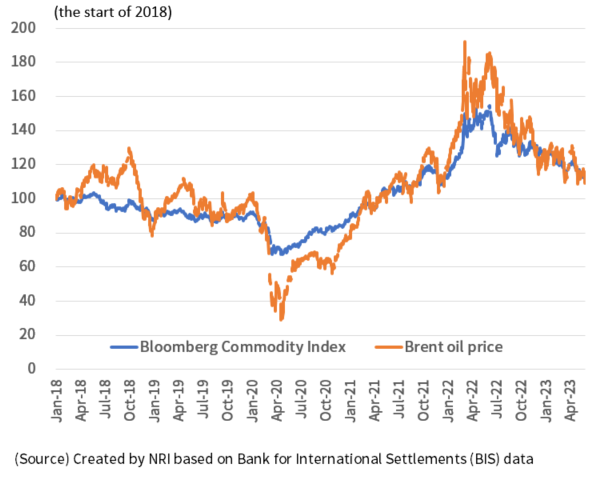

Crude oil prices peaked out in the summer of 2022, and subsequently they have been on a declining trend. The overall market for commodities including energy, metals, and food also peaked out in the summer of 2022, as can be confirmed from the Bloomberg Commodity Index, the CRB Index, and other indicators (Fig. 1).

As a result of the growing infection risk and infection control measures, the Asian region—especially China—saw factory operations shut down and port functions cease. Consequently, global supply chains were severely disrupted. The semiconductor shortage in particular hindered the production of automobiles and various other products, and supply shortages drove prices upward.

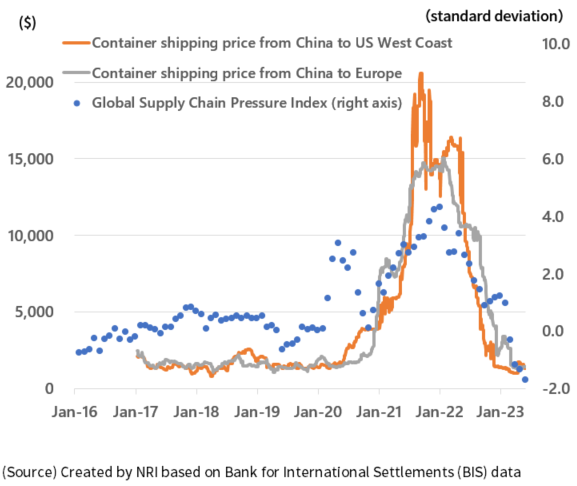

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), shipping costs for containers from China to Europe and the US skyrocketed because of supply constraints brought about by the decline in port operations in China from COVID-19 countermeasures. However, once 2022 came around, those costs rapidly declined, indicating that the supply chain turmoil reached an end (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1: Crude Oil Prices / Commodity Market Peaked Out

Fig. 2: Supply Chain Disruptions At An End

Structural changes in consumer behavior brought on by the Coronavirus Shock

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on consumer behavior. Concerns over infection risk led consumers to forego travel, dining out, amusement, and other behaviors involving face-to-face contact, and instead they stayed home and increased their at-home consumption. This is what has been called “nesting consumption”.

As a result, there was a dramatic rise in demand for foods used in cooking at home instead of dining out, and also for furniture, home appliances, and daily necessities as well as online shopping in order to enhance home life. This reduced the proportion of consumer spending made up by the consumption of services, while raising the proportion made up by the consumption of goods.

The growth in demand for consumable goods has revitalized production activities in the manufacturing sector, boosted demand for the raw materials, electricity (energy used to generate power), and shipping required for those activities, and pushed prices up for all of those. This is conceivably one factor behind soaring prices.

However, with the infection risk gradually declining, consumers are once again partaking of services involving in-person contact such as travel, dining out, and amusement, and this has resulted in weaker demand for goods. This would seem to be what is reducing the upward pressure in the prices of goods.

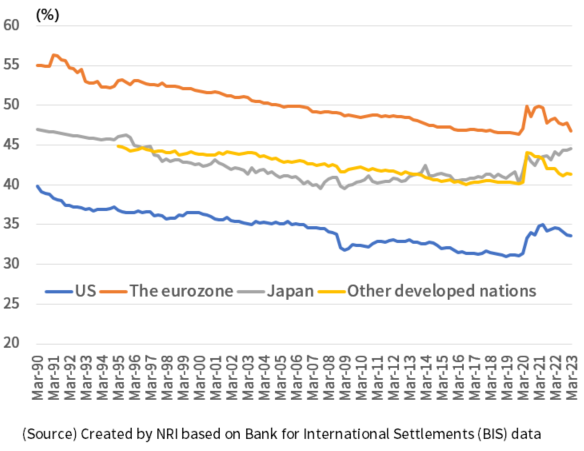

Looking at the makeup of nominal consumer spending, we see that in many advanced countries, the ratio accounted for by the consumption of goods—which had temporarily risen—has fallen (Fig. 3). Yet its level has not yet returned to the level before that increase, or to its pre-increase trend, and it is possible that the ratio made up by goods consumption is now structurally higher than before. However, the fact that this ratio has been declining has likely contributed to the stabilization of commodities prices.

On the other hand, the ratio of goods consumption in Japan is continuing on its upward trend, suggesting that commodities prices here could potentially take longer to stabilize than in other developed countries.

Fig. 3: Goods Consumption as a Percentage of Nominal Consumer Spending

Long-term inflation expectations have relatively stabilized

In contrast to goods prices which have visibly begun to stabilize, the rate of increase in the prices of services has remained high, and this has prevented the overall inflation rate from falling. In some sense, perhaps, rising prices have pushed wages up, and this in turn has led businesses to raise their prices, especially in the services sector. This is what is called the secondary effect of inflation.

It should be noted, however, that the tendency for the prices of services to lag behind goods prices is a phenomenon seen both in inflationary phases and deflationary phases, and this instance is by no means an exception.

In addition, thanks to the success of the significant monetary tightening policies aimed at restoring price stability, in the US and the UK especially, long-term inflationary expectations have remained stable, at levels relatively near the inflation rate trends seen before the current price surges.

The actual inflation rate would seem to depend significantly on the long-term inflationary expectations of businesses, households, and financial markets, and as such, the stability of these long-term inflationary expectations has likely reduced the risk that an upswing in the inflation rate will firmly take root.

Central banks determined to restore price stability soon, even at the expense of the economy

The central banks of many major countries in Europe, the US, and elsewhere are approaching monetary policy with the strong intention of quickly achieving their price targets and preventing these price surges from becoming entrenched, even at the expense of their economies. As a result, there would seem to be a mounting risk that the economy will become a victim of excessive monetary tightening, which is known as “overkill”.

Some are also warning that while monetary tightening will cause economic conditions to worsen, we could see a sustained uptick in the inflation rate and find ourselves in a state of stagflation. However, in actuality, the chances that inflation will remain significantly high while the economy slows down are probably not very strong.

A low inflation, low interest rate environment will return

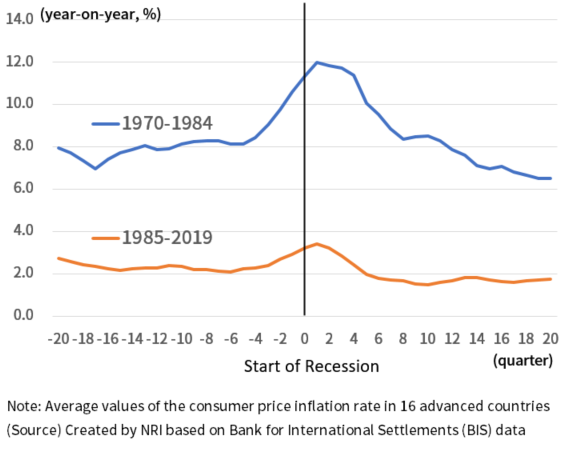

Fig. 4 shows the average value of the inflation rates in advanced countries immediately before and after recessions during two periods: from 1970 to 1984 and from 1985 to 2019. In these cases, once a recession hit, it took 12 quarters and five quarters in these respective periods for the inflation rate to fall back down to the level seen six quarters before the start of the recession (or, generally speaking, the level before prices began skyrocketing).

If monetary tightening in response to soaring prices does bring on a recession, in light of these past examples, it would take between around one and three years for the inflation rate to drop down to its previous level.

Another thing worth noting is that for both of these periods (from 1970 to 1984 and from 1985 to 2019), the inflation rate in the wake of the recession tended rather to fall below the level from prior to the start of the recession.

Given these points, it is hard to fathom that the global economy, having experienced a lengthy low-inflation phase, would be triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the like to undergo a sudden structural change making high inflation the norm.

We should note that while this would take several years to happen, large-scale monetary tightening would also have a certain driving force of economic slowdown, spurring the global economy to revert to a traditional low inflation environment. That means a return to a low interest rate environment, as well.

Fig. 4: Inflation Rate Before/After the Start of Recessions

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.