Have we already seen the worst of price surges?

According to the July nationwide consumer price statistics released by the Ministry of Internal Affairs on August 18, in response to falling electricity prices and other factors, the Core CPI (excluding fresh food) showed a rise of 3.1% compared to the same month last year, which was lower than the 3.3% year-on-year increase seen in June. This development tracked with the Tokyo CPI from mid-July, and was in line with previous expectations.

The Core CPI has been on a downward trend ever since it peaked this past January with a year-on-year rise of 4.2%. While price trends going forward may well depend heavily on the government’s anti-inflation measures, given that the rise in import prices (the root cause of soaring prices) has already run its course, and that import prices in July were significantly lower year-on-year (down 14.1%), one might say that we’ve already gotten through the worst of the price surges.

Companies have continued their tendency to raise food prices, but food prices excluding fresh foods have now shown a year-on-year rise of 9.2% for three months in a row, and thus the pace of the increase has begun showing signs of having peaked.

According to the July CPI, thanks to the rebound of domestic travel and higher numbers of travelers coming from overseas, along with the peaking out of nationwide travel assistance, accommodation fees boosted the CPI by 0.10% versus the same month last year. On the other hand, the falling prices of electricity bills caused the CPI to drop 0.18% year-on-year. That said, within the category of energy prices, gasoline prices rose 2.5% month-on-month, leading to a rise of 0.06% in the CPI year-on-year.

While there is a strong chance that the inflation rate will follow this declining trend in the times ahead, for the moment it will depend significantly on what happens with gasoline prices and with electricity and gas prices, which are highly susceptible to the effects of government policies.

Gasoline prices around 196 yen at end of August, around 199 yen at end of September

The price of gasoline as of August 14, according to the report released by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry on August 16 (national average, regular) was 181.9 yen/liter, even higher than the 180.3 yen/liter seen the week prior as of August 7. That marked the 13th straight week in which prices at the pump rose. The highest price ever seen thus far was 185 yen, back in August 2008, but the latest figure has come rather close to that level.

The government introduced a subsidy system at the beginning of last year in order to curb the rise in retail gasoline prices. Since June, it has slowly been phasing out those subsidies, which are now on track to be eliminated at the end of September. As a result of these gradual subsidy reduction measures, the price of gasoline—which had long been maintained at around 168 yen—has recently been climbing as high as around 182 yen.

Recent trends in the yen-denominated price of crude oil suggest that gasoline prices, which had been kept down because of those subsidies, will rise to around 196 yen at the end of August.

In a scenario where crude oil prices and the dollar/yen exchange rate remain unchanged at current levels as subsidies are increasingly scaled down, it’s expected that gasoline prices at the end of September when the subsidy system is scheduled to be completely abolished will reach around 199 yen. Conditions are such that the slightest changes in crude oil prices and exchange rates could easily send gasoline prices as high as the 200-yen range.

In the case of rising crude oil prices and a depreciating yen, gasoline prices could hit 212 yen at the end of September

Going forward, if WTI crude oil prices should rise from their current level of around $81 per barrel to around $85 per barrel, and the yen’s depreciation were to send the dollar/yen exchange rate from 145 yen per dollar to 150 yen per dollar, then gasoline prices at the end of September would reach as high as 212 yen or thereabout.

A rise in gasoline prices would affect price conditions, and through that, would probably deal a blow to consumer spending. If the price of gasoline were to rise from the level of around 168 yen seen before subsidies started getting phased out to around 199 yen, consumer prices would get pushed up by 0.34% in total, whereas if the price of gasoline reached as high as around 212 yen, they’d be bumped up by 0.48%. In addition, if we try to calculate how rising gasoline prices would affect real personal spending (annual) in these two scenarios (ESRI Short-Run Macroeconometric Model (2022)), the impact comes out to an annual drop of 0.16% and 0.22%, respectively.

If the rise in gasoline prices leads the inflation rate to take longer to fall, there will be heightened fears that the decline in real wages—which by July had already lasted for 15 straight months—could be even longer-lasting, potentially leading consumers to suddenly curb their spending.

Japan seeing an uptick in its long-term inflation rate

In its Outlook Report published on July 28, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) revised its Core CPI forecast for FY2023 to a rise of 2.5% year-on-year, which was substantially higher than the 1.8% rise reported the previous time in April. However, the actual Core CPI for FY2023 has surpassed that level, and the decline in the rate of inflation appears to be happening at a more gradual pace.

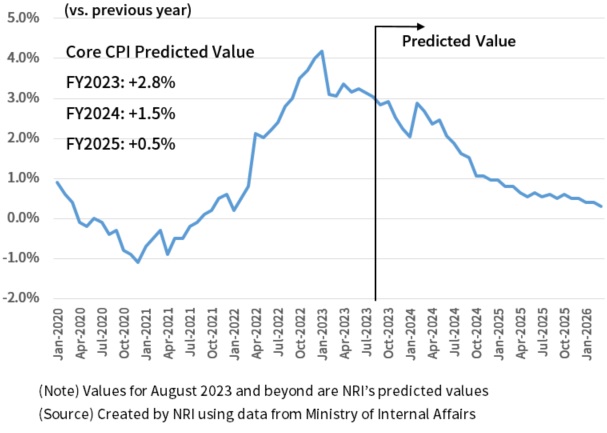

I expect the FY2023 Core CPI to rise by 2.8% compared to the previous fiscal year. That said, I foresee that the rate of inflation will continue on its downward trajectory, rising by 1.5% in FY2024, followed by a rise of only 0.5% in FY2025, dropping to levels well below the BOJ’s 2% price stability target (Graph).

Incidentally, if we compare this to the situation in the US, for example, what’s noteworthy is that long-term inflation expectations among individuals in Japan are seeing a major uptick. According to calculations by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), expectations have risen as much as three percentage points since the end of 2020, even having risen five percent in recent months.

The fact that unlike the central banks in Europe and the US, the BOJ (with its particular focus on the 2% price stability target) has refused to revise its monetary policy even in the face of the rising inflation rate, and has allowed long-term inflation expectations to rise, has likely had a major effect in this regard. Given the foregoing, inflation rates in the West could fall relatively rapidly going forward, whereas Japan is probably at risk of having its inflation rate take longer to come down.

Graph: Core CPI Outlook

The BOJ should discard its commitment to the 2% price stability target and embark on full-scale policy revisions

While some are of the opinion that substantial increases in long-term inflation expectations are desirable for achieving the 2% price stability target, I believe that idea could be dangerous. The recent major upswings in the inflation rate and in long-term inflation expectations, dissociated from the growth potential of the Japanese economy, could compromise Japan’s economic stability.

For example, given that corporate long-term inflation expectations likely haven’t risen as much as expectations among individual consumers have, it’s conceivable that companies will remain cautious about raising wages significantly, and as a result the wage growth rate won’t keep pace with the high long-term inflation expectations among consumers going forward. If that trend becomes apparent, there’s a risk that individual consumers may abruptly refrain from consumption.

The BOJ has stated repeatedly that achieving a sustainable and secure 2% price stability target accompanied by wage growth is still a long way off. Even if this judgment is correct, and the recent rise in the inflation rate is merely a temporary uptick, achieving the 2% price stability target in the short term certainly seems difficult.

However, this 2% price stability target that the BOJ was forced to adopt 10 years ago under political pressure was never appropriate in the first place. Even now it remains too high given the actual potential of the Japanese economy. Rather than stick to the 2% price stability target, the BOJ should adopt a stronger stance to secure medium- and long-term price stability in order to stabilize the Japanese economy and people’s livelihoods. As one part of that, perhaps it ought to go beyond the tweaks made in July to its Yield Curve Control (YCC) program, and quickly embark on more fully-fledged policy revisions including the elimination of negative interest rates.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.