At a Monetary Policy Meeting held on July 30 and 31, 2024, the Bank of Japan will announce concrete measures for scaling back its government bond purchases. The BOJ’s move to draw down its JGB purchase amount just four months after eliminating its negative interest rate policy in March of this year is faster than initially imagined, but it could be that the yen’s ongoing depreciation led it to push up the timetable.

Additional rate hikes to come no sooner than September?

The Bank of Japan adopted a two-stage approach here, deciding at its June meeting

that it would be trimming back its JGB purchases, and is now poised to announce the detailed measures

involved at its upcoming July meeting. The reasoning behind this was to listen first to what market

participants were saying and only then decide carefully on specific measures, as Governor Ueda

explained.

However, the Governor’s statements, for instance that the size of the reduction would be

"considerable”, give the impression that the BOJ has already settled on a concrete framework for

this scaling back even before soliciting market participants’ views.

One gets the sense that this announcement of detailed measures in July is partly intended to buy time.

Buying time, as it were, would mean adopting policy measures in a piecemeal manner to keep constraints

on the yen’s depreciation in effect for as long as possible.

At the April meeting, Governor Ueda’s remarks were taken to be permissive toward the weakening

yen, at which point the yen continued to depreciate down to 1USD/160JPY. The BOJ, viewing this as a

misstep, would now seem to be conducting its monetary policy with a focus on curbing the yen’s

ongoing downward slide, which is a factor behind high prices.

If the Bank is aiming to restrain the yen’s decline by making incremental policy adjustments, then

it’s possible that at the upcoming meeting in July it won’t make any additional rate hikes

to coincide with this drawdown in JGB buying. Further, there’s a risk that enacting two major

policy changes at the same time could throw the financial market into chaos, and July would still be

somewhat too soon for the data to confirm how far wages will rise following the annual springtime labor

negotiations between unions and companies, as well as to know what the spillover effects from wages on

prices will be, for example. Given the foregoing, I believe we should expect any additional rate hikes

to come in September at the earliest.

Is the BOJ searching for its own style of quantitative tightening?

Given how emphatically Governor Ueda stressed that the scale of the reduction

would be “considerable”, the monthly JGB purchase amount of around six trillion yen that was

decided on in March could possibly be cut back to around three to four trillion yen.

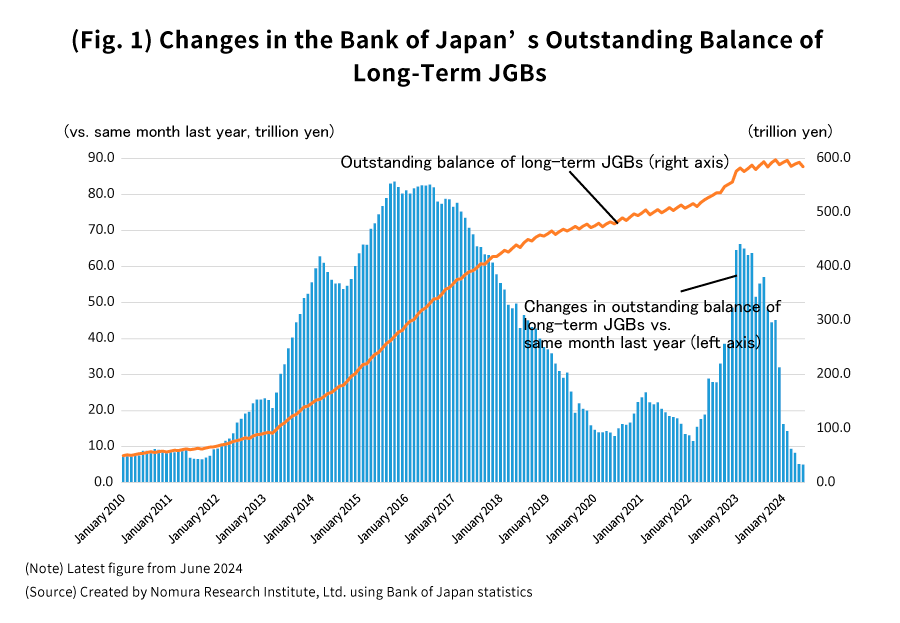

Since a monthly JGB purchase amount of around six trillion yen roughly matches up with the monthly

redemption amount of JGBs held by the Bank of Japan, the outstanding balance of JGBs has stayed nearly

the same up to now (Fig. 1). If the purchase amount were to be scaled back to only around three to four

trillion yen per month, the Bank’s outstanding JGB balance would clearly begin to drop. This is

the beginning of what’s known as quantitative tightening (QT).

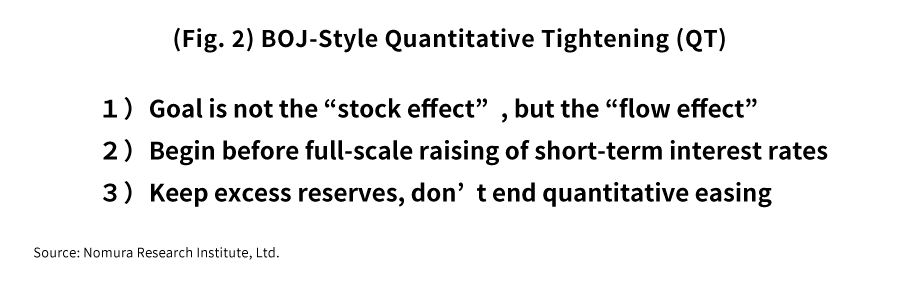

When contrasted with the quantitative tightening precedent established by the FRB

(US Federal Reserve Board), the quantitative tightening that the Bank of Japan is trying to implement

differs in the following three respects, which comes as a surprise (Fig. 2).

First, Governor Ueda made it clear that the Bank’s prime concern was not the scale of the

reduction of its JGB balance (i.e., the “stock effect”), but rather the size of its JGB

purchases (i.e., the “flow effect”). Now, even if the JGB purchase amount were to be reduced

and then maintained at a certain level, since the redemption amount would still fluctuate from day to

day, the pace of the balance drawdown would no longer be constant. Since the impact of quantitative

tightening on the JGB market would mainly be determined by the changes in the balance of JGBs held by

the Bank, it’s questionable whether the flow effect is really an appropriate goal.

Second, the FRB’s policy was to raise short-term interest rates by a certain amount and only then

scale down the balance of bonds, i.e., begin quantitative tightening. Yet the Bank of Japan is already

set to embark on a course of quantitative tightening while short-term interest rates are still at around

0%.

Third, Governor Ueda stated that the Bank was not working from the assumption that having no excess

reserves would be desirable. This means that even after the Bank goes ahead with reducing its JGB

buying, it will retain a considerable outstanding balance of JGBs. If the Bank were to keep a

significant amount of JGBs on its balance sheet and to maintain its excess reserves, then its

quantitative easing policy would persist onward.

These policies might be intended to reduce the risk of a rise in long-term interest rates, but one must

wonder why the Bank would shift toward normalizing its monetary policy but choose not to fully normalize

quantitative easing (a balance sheet policy). I would like to hear the Bank of Japan explain this point

in some detail.

The drawdown in JGB purchases won’t significantly affect long-term interest rates

If the Bank of Japan does begin drawing down its JGB purchases in July as

described, what sort of effects will that have on long-term interest rates? While there is some

uncertainty, long-term interest rates likely won’t be all that affected.

In 2013, the Bank of Japan began making large-scale purchases of JGBs under a “quantitative and

qualitative monetary easing” framework, but this didn’t lead long-term interest rates to

fall substantially. This is arguably because at the time that it embarked on that policy, there was

already little room left for long-term interest rates to come down.

The Bank of Japan has explained that its JGB purchases drove down long-term interest rates by around1%,

but in fact the effect seems to have been smaller than that.

Although the Bank of Japan bought JGBs from banks and in return supplied them with money (current

account deposits at the Bank), when interest levels are sufficiently low, even if money is supplied it

won’t bring interest rates down and then economic effects won’t materialize. This is

what’s called a “liquidity trap”, and it’s possible that the market had already

fallen into that very situation.

For this reason, it’s conceivable that even if the Bank conversely cuts back on its JGB buying and

reduces the money supply, it won’t lead long-term interest rates to rise by all that much.

I think that in the time ahead, what will have an impact on long-term interest rates and consequently

help things reach a stable equilibrium isn’t quantitative tightening, but rather is the extent to

which short-term interest rates can be raised.

The increase in short- and long-term interest rates won’t be great, and their economic impact will be limited

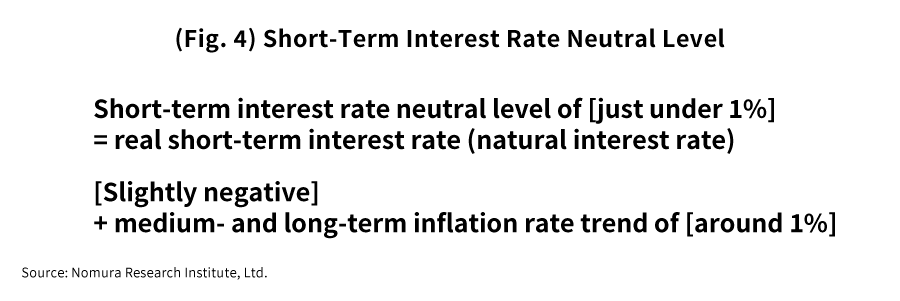

The level at which (nominal) short-term interest rates would be neutral in terms

of their effect on the economy is determined by the total of the level of “real short-term

interest rates”—which have a neutral economic effect and are known as “natural

interest rates”—and the level of medium- and long-term inflation rate trends. While

it’s difficult to accurately measure the level of natural interest rates, according to the Bank of

Japan, multiple estimations indicate that it’s in a range of around +0.5% to -1.0%. Now,

let’s assume the level is slightly negative.

In that case, if the medium- and long-term trend in the inflation rate hypothetically were to match the

2% price stability target, then the neutral level of short-term interest rates, and in turn the terminus

of their rise, would be slightly under 2%.

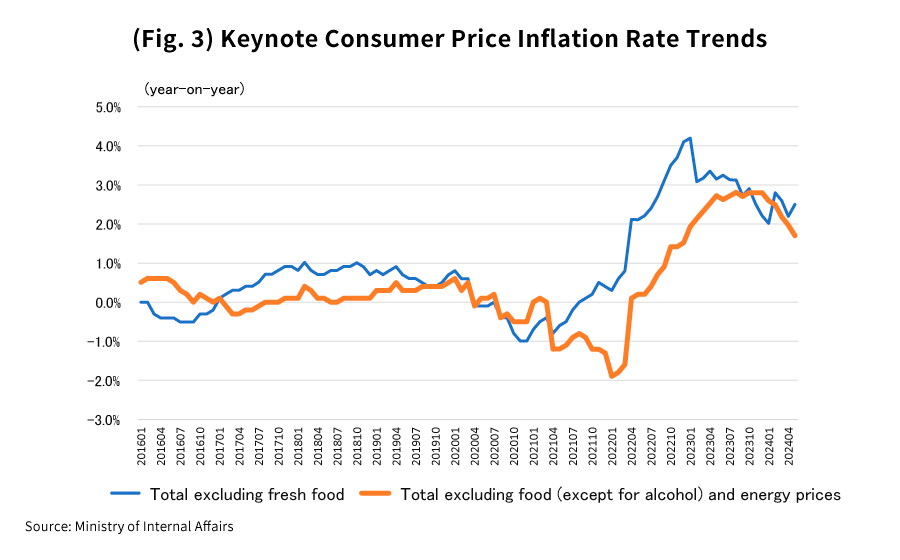

Yet in actuality, the recent uptick in prices would seem to be largely attributable to the rise of

overseas market conditions and the transient rise in import prices caused by the depreciation of the

yen. If we look at the rate of increase in the keynote consumer price index excluding food (except for

alcohol) and energy prices, we see that it’s already clearly starting to come down, and the most

recent value from May was +1.7% year-on-year, which was below the price stability target of 2%.

Ultimately this figure is expected to settle at around the level of 1%. (Fig. 3)

In this scenario, the neutral level for short-term interest rates—and their terminus—would

be slightly under 1%, with 10-year JGB yields settling at roughly 1%, which wouldn’t be very much

different from where they are currently. (Fig. 4)

Even if the Bank of Japan were to simultaneously raise short-term interest rates and draw down the

amount of its JGB purchases, the extent to which short-term interest rates would rise would be

relatively small, and as long as long-term interest rate levels also do not change significantly from

what they are now, the impact of these policies on the Japanese economy wouldn’t be terribly large

either.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.