At a meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) held on September 18, 2024, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board (FRB) decided to lower the policy interest rate by 0.5%. This sizeable rate cut is the FRB’s first in four and a half years since March 2020, when the policy rate was abruptly lowered to zero in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. As a policy shift, the FRB’s move is a symbolic indication that the aims of the U.S. and world economies have transitioned from price stabilization to avoiding economic downturn. However, the rate cut also has created a historically anomalous situation, in which the fiscal policies of Japan and the U.S. are moving in opposite directions.

FRB embarks on dramatic 0.5% rate cut

In response to alarming consumer price spikes precipitated by the Covid-19

pandemic and the war in Ukraine, between March 2022 and July 2023 FRB increased interest rates a total

of 11 times, bringing the policy rate to its highest level since 2001.

More recently, however, the rate of inflation has been on a steady decline, while indicators of weakness

in the labor market have risen. Acknowledging these trends, FRB Chair Jerome Powell remarked at this

August’s Jackson Hole Economic Symposium that “the time has come for policy to

adjust”, strongly hinting at a shift toward rate cuts.

Immediately before the FOMC, opinions in financial markets regarding the potential size of the cuts were

broadly divided between 0.25% and 0.5%. Typically, changes in the FRB’s policy rate are made in

increments of 0.25%. For example, in the case of the rate increases begun in March 2022, while the FRB

ultimately imposed a series of atypically large 0.75% rate increases out of a sense of urgency over the

delayed response to rising inflation, the first hike made was only 0.25%. Likewise, both when rate

increases were initiated in 2016 and when rate cuts were initiated in 2019, the initial changes were

0.25%. The 0.5% rate cut instituted at the latest FOMC thus can be considered highly atypical in scale.

Risks shift from upswing in prices to downturn in the economy

The large cut imposed by the FRB appears to have been precipitated by the view

that government policy needs to keep up with economic reality. Many observers reflecting on the rate

increases begun in March 2022 have concluded, in retrospect, that the delayed response to consumer price

spikes made a series of dramatic 0.75% rate increases inevitable, and these regrets may inform the

current move toward large rate cuts. In addition, in the event that there is a significant downturn in

economic indicators, particularly around hiring, the cuts could act as insurance against criticism of

the FRB for being slow to react.

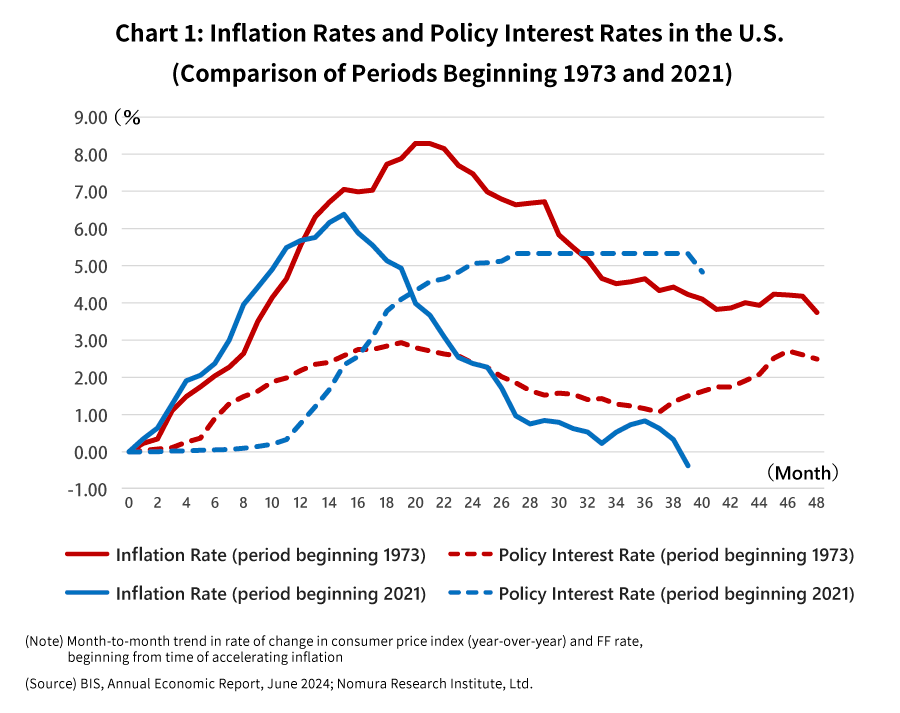

During the 1973 oil crisis, FRB shifted course into policy rate reductions before the rate of inflation

had peaked. This policy may have allowed high inflation to become entrenched. Tempered by these lessons,

the FRB’s approach to the current situation was to continue raising the policy rate and keep

interest at a high level for more than a year after the inflation rate peaked and shifted downward

(Chart 1). This seems to have contributed to a steady decline in inflation, and by the latter half of

2025, the inflation rate is expected to fall to the FRB’s 2% target rate.

Another possibility, however, is that the effects of the significant monetary tightening imposed to

ensure price stabilization, and of the length of time this tightening was maintained, will produce an

economic downturn going forward. For now, there is no clear answer to the question of whether the

economy has been sacrificed at the altar of price stabilization.

Japanese and U.S. fiscal policies are moving in opposite directions

Meanwhile, this March, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) ended its negative interest policy

and began normalizing fiscal policy, resuming policy interest rate increases in July. Thus, with the

FRB’s decision to reduce the policy rate, the fiscal policies of Japan and the U.S. have begun

moving in opposite directions. There is little historical precedent for this situation.

Customary practice at the BOJ has long been to follow the fiscal policy of the FRB. One reason for this

is that Japan’s economy is strongly influenced by the U.S. economy, and this intense economic

interdependence has meant that the fiscal policies of the two countries readily move in lockstep.

Another reason, however, is that a stable dollar-yen exchange rate is extremely important for Japan from

the perspective of trade activity and consumer prices, and the BOJ traditionally has ensured this

stability by hewing closely to FRB fiscal policy, out of concern for avoiding major fluctuations in the

dollar-yen rate.

These habits, however, appear to be eroding. In response to the global consumer price spike, the FRB and

other major central banks moved in 2022 to increase policy interest rates significantly, but the BOJ

bucked this trend by maintaining a policy of monetary easing. Now, the FRB has moved to cut its policy

interest rate as rates are increased at the BOJ. The BOJ has set a lofty CPI target of 2% and has been

steadfast in pursuit of that goal – a reflection of the stark variance at which domestic and

international fiscal policies now operate.

As the directions of Japanese and U.S. fiscal policies diverged, the dollar-yen exchange rate, which is

sharply affected by the difference in interest rates between the two countries, began to experience

major fluctuations. When the FRB started raising the policy rate in March 2022, a trend toward a strong

dollar and a weak yen rapidly gathered strength in the exchange market, dropping to a low of 161-yen

level against the dollar in July 2024.

This rapid decline in yen value coincided with a worldwide increase in energy and food prices,

resulting, in 2023, in Japan’s biggest jump in inflation in 40 years. This created a strong

headwind against personal consumption.

However, as the observation that Japanese and U.S. fiscal policies are moving in opposite directions has

become more compelling, the dollar-yen exchange rate has reversed course in the yen’s favor,

producing a rebound in yen value to around 139.5 against the dollar on September 16 of this year. It is

not yet fully foreseeable how international capital flows – and, by extension, exchange rates

– will be affected by the anomalous condition of Japanese and U.S. fiscal policies moving in

opposite directions. This uncertainty may have been one of the causes of the biggest-ever drop in the

Nikkei Stock Average that occurred this August.

Underlying trend of inflation in Japan turns downward

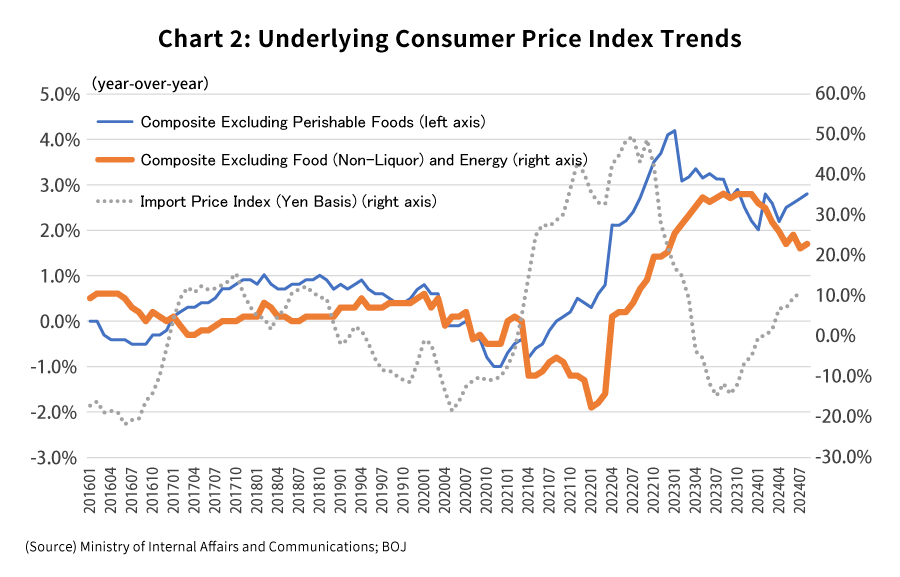

Japan’s nationwide consumer price index (excluding perishable foods) was up

2.8% year-over-year in August, continuing its trend of exceeding the BOJ’s 2% CPI target. However,

this uptick in consumer prices appears to be largely the result of the temporary factor of rising import

prices. The increase in food and energy prices overseas essentially came full circle in 2022; since

then, rising import prices in Japan have been mainly the result of the ongoing depreciation of the yen.

An examination of underlying price trends that are not directly affected by rising import prices or by

government subsidy systems for electric/gas bills or gasoline draws our attention to the

“composite index excluding food (non-liquor) and energy”. This index has trended downward

since the beginning of the year, posting a year-over-year figure of +1.7% in its most recent result this

August, the indicator’s fourth consecutive month under 2%. This means that the impact of rising

import prices on underlying price is already declining (Chart 2).

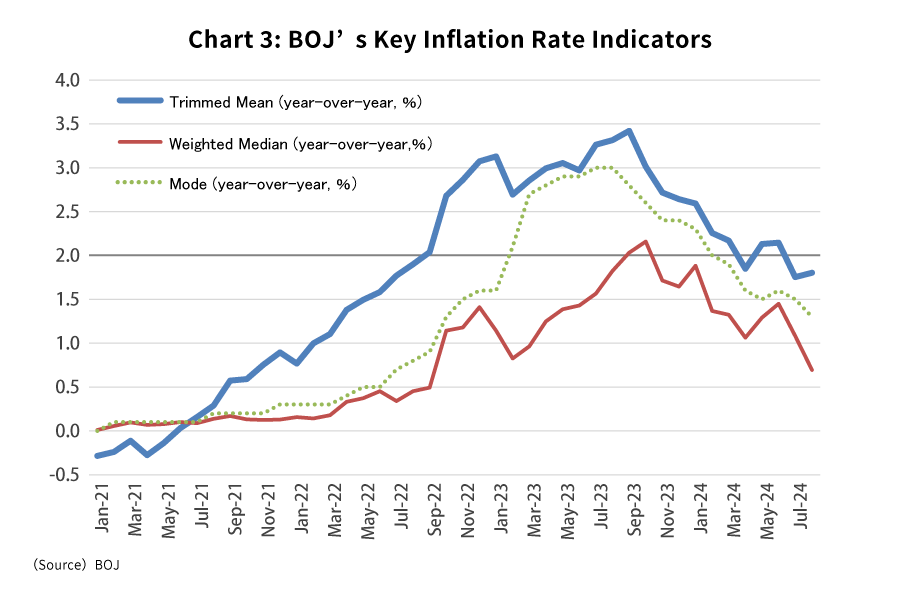

In addition, of the three key inflation indicators based on consumer price statistics that were

announced by the BOJ on September 25, the weighted median and mode have both fallen significantly, and

all three indicators, including the trimmed mean, are trending below the BOJ’s 2% target (Chart

3).

If the impact of the decline in import prices due to the rising yen adds weight to these trends going

forward, underlying inflation rates will continue to decline and the consumer price index will stabilize

at a sustainable level around 2%, making realization of the 2% CPI target a routine occurrence.

It appears likely that the fiscal policies of Japan and the U.S. will keep moving in opposite

directions, and that, buoyed by the ongoing correction of the weak yen, Japan will see a downward trend

in inflation as well, albeit later than in the U.S.

Additional rate hikes from the BOJ would be pushed back

At a press conference held after the Monetary Policy Meeting on September 20, BOJ

Governor Kazuo Ueda stated that, because of the yen’s continuing increase, “the risk of an

inflation overshoot that was noted in July has diminished significantly”, adding that “we

have some time to decide on policy.” Governor Ueda also cautioned about the risk of a downturn in

the U.S. economy. These remarks amount to a manifestation of intent by the BOJ not to rush further rate

hikes. However, the BOJ’s attitude also could be the product of concern regarding the

indiscernibility of how financial markets will be affected by the unfamiliar condition of Japanese and

U.S. fiscal policies moving in opposite directions.

In addition, since its inauguration, the new Ishiba administration repeatedly has made cautious

statements regarding policy rate hikes by the BOJ. This too could act as a constraint against further

hikes by the BOJ.

Moreover, given the downward trend in the key inflation indicators described above, there is a growing

risk that any additional rate hikes by the BOJ will be belated reactions. Currently, the BOJ is

considering a normative scenario in which it will impose additional rate hikes next January, but it

seems that these could be pushed back even more.

If the U.S. economy declines more than expected and the rise in the yen accelerates, the downside risks

to the Japanese economy will become more severe. In such a case, it is conceivable that the BOJ’s

fiscal policy management, like that of the FRB, will shift focus gradually from achieving CPI targets to

avoiding economic downturn. It is easy to imagine a scenario where such changes would do away with the

historically anomalous condition of Japanese and U.S. fiscal policies moving in opposite directions.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.