It has been nearly a year since the Bank of Japan did away with its negative interest rate policy on March 19, 2024, thus embarking on the normalization of its monetary policy. In this time, the Bank of Japan has made two additional policy interest rate hikes, and has been steadily proceeding with normalizing monetary policy in various ways, including by starting to draw down the amount outstanding of its JGB holdings, which is also known as quantitative tightening (QT). While this is to be lauded, I do believe some challenges still remain when it comes to their communications to the public. Medium and long-term inflation expectations (i.e., the expected inflation rate) come very much into play in this regard.

The underlying trend in inflation as reflected in consumer prices still has not reached 2%

Many people are probably wondering why this 2% price stability target has not yet been achieved while the actual inflation rate remains above 2%. And there are probably also those who fear that this policy stance by the Bank of Japan will only send the inflation rate even higher, putting pressure on people’s lives.

The Bank of Japan believes that once the actual inflation rate not only reaches 2%, but remains there over the medium and long term, its price stability target will then finally have been achieved. Furthermore, it has focused its attention on medium- and long-term inflation expectations, and seems to make its determinations on that basis regarding the current underlying trend of inflation in consumer prices.

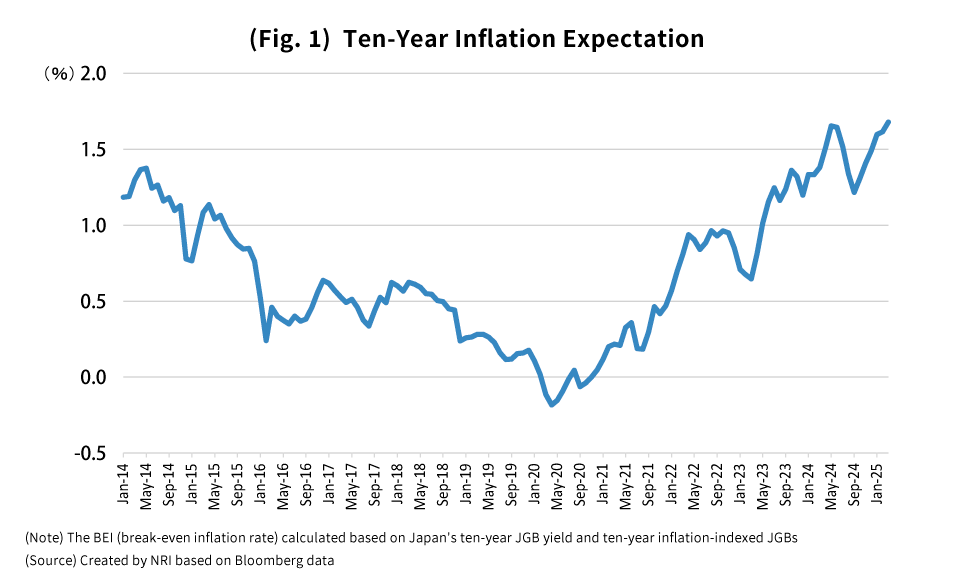

One of the indicators of medium- and long-term inflation expectations on which the Bank of Japan appears to be placing great importance is the inflation expectation in the financial market, as calculated based on inflation-indexed JGBs. The ten-year inflation expectation has been on an upward trend ever since 2021, and currently sits at around 1.7% (Fig. 1).

Where is the terminal rate?

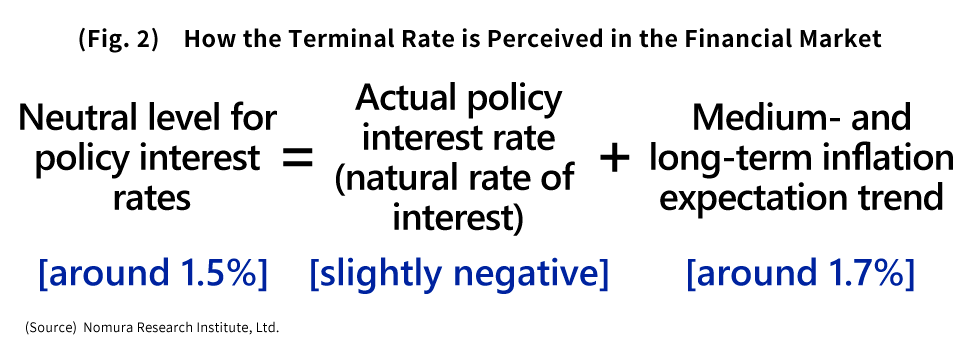

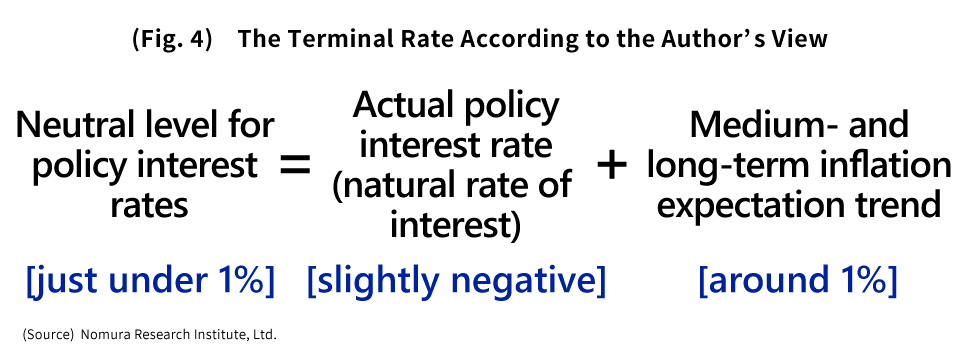

This is because if we assume that the Bank of Japan will raise policy interest rates to a neutral level with respect to economic activity and prices, and that this level will be the terminal rate, then presumably it will be a matter of adding together the neutral real interest rate (nominal policy interest rate minus inflation expectations)—or the so-called “natural rate of interest”—and the medium- and long-term inflation expectation trend.

While we do not know for sure what the level of the natural rate of interest is, several estimates given by the Bank of Japan put it within the range of +0.5% to -1.0%, which averages out to be slightly negative. If we add to this the 1.7% figure representing the current inflation expectation for 10-year inflation-indexed JGBs (one of the indicators of medium- and long-term inflation expectations), then this works out to a terminal rate of around 1.5% (Fig. 2).

Inflation expectations tend to track the actual inflation rate

However, this view in the financial market would seem to have gone a bit too far. The medium- and long-term inflation expectation on which the Bank of Japan has been focused appears to be heavily influenced and swayed by actual price developments. Rather than the sort of causal relationship being assumed by the Bank of Japan, in which medium- and long-term inflation expectations (which are highly susceptible to the effects of monetary policy) determine inflationary trends, it seems to me that the reverse causality is true, and the actual inflation rate instead determines medium- and long-term inflation expectations.

In fact, in the midst of this ongoing extraordinary easing, the market’s inflation expectation has continued to fall. On the other hand, back in 2021 when the market’s inflation expectation switched to an uptrend, that reversal was triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine, which sent prices soaring worldwide (Fig. 1). Rather than supposing that the market’s inflation expectation reflects the effects of monetary easing, we should probably say that changes in the market’s inflation expectation strongly tend to track those in the actual inflation rate.

The inflation rate is gradually falling

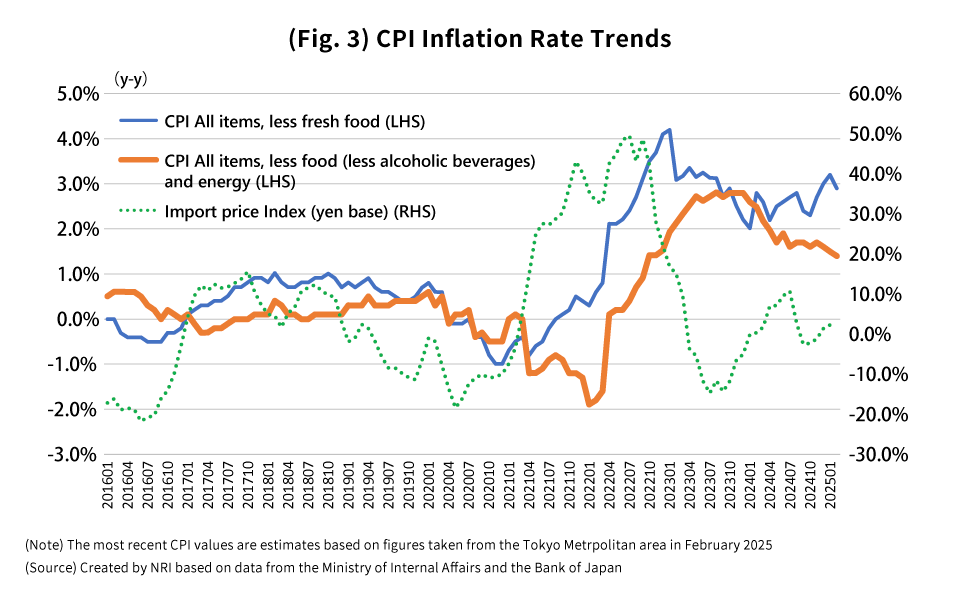

Now, when we look closely at the “All items, less food (less alcoholic beverages) and energy” index, which does not include those factors and which is a better indicator of underlying price trends, we see a clear downward trajectory. That index is estimated to have been at +1.4% over the previous year back in February, and thus to have fallen down to roughly half of the near-3% level it hit at one point (Fig. 3).

In addition, we are also seeing a downtick in the “services price” index, which in the Bank of Japan’s eyes holds the key to achieving a virtuous cycle between prices and wages. There is still no apparent path by which this virtuous cycle can be achieved, which would thereby allow the inflation rate to hold steady at around 2%.

Have the financial market’s policy interest rate hike speculations gone too far?

Given that the “All items, less food (less alcoholic beverages) and energy” index is already projected to fall to the range of +1.0-1.5% year-on-year, it could well fall at least down to around 1% in the not-too-distant future.

Furthermore, if we assume hypothetically that this is where medium- and long-term inflation expectations will end up landing, then the neutral level for policy interest rates, i.e., the terminal rate, will come out not to around 1.5%, but rather just slightly under 1% (Fig. 4). The Bank of Japan, accounting for the possibility that medium- and long-term inflation expectations could tick down even further going forward, will likely be cautious about raising policy interest rates as it tries to work out where this final landing spot will be.

In light of these points, the financial market’s current expectation that a policy interest rate hike will be coming soon sometime around June, as well as its speculations that the level of this rate hike will far surpass 1%, have perhaps gone too far. I would rather expect that the next policy interest rate hike will come this September, or if any sooner, no earlier than July, and that policy interest rates will peak at 1% in the middle of next year.

Assuming that this is what lies ahead for policy interest rates, then I would suppose that the long-term interest rates we have seen rise significantly of late may also have gone a bit too far from a somewhat longer-term perspective.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.