The tariff talks between Japan and the U.S. that had been ongoing since April suddenly reached an agreement on July 22 (U.S. time). Given how deeply divided the two countries seemed to be over the issue of tariffs, it was entirely unexpected for an agreement to be achieved at this time. The 25% reciprocal tariff rate imposed on Japan that had been unilaterally announced by the Trump Administration in July is being lowered to 15% with this new agreement, and similarly, the automotive tariffs that had been in effect since April will also be brought down from 25% to 15%. On July 31, President Trump then signed an executive order further modifying reciprocal tariff rates on various countries, including Japan. Following this move, the new 15% reciprocal tariff rate on Japan went into effect on August 7. However, the timing at which the automotive tariffs will drop down to 15% is yet undecided.

Negative Economic Effects of the Tariffs to Persist

Meanwhile, although the Trump Administration has maintained during its bilateral talks that automotive tariffs (being industry-specific) would not be covered in those talks, it has now assented to Japan’s request for the automotive tariff rate to be lowered, which means that it has been somewhat conciliatory to Japan. One imagines that Japan’s massive U.S. investment plan, which I discuss below, was a major factor in drawing this concession out from the Trump Administration and making this agreement even possible.

With this latest agreement, the impact from the Trump tariffs overall on Japan’s real GDP (around one year) would come out to a 0.55% drop. Until the automotive tariffs are brought down to 15%, the tariffs will mean a 0.60% drop.

Compared to the 0.85% hit that would have resulted back when the reciprocal tariffs were raised to 25%, the adverse effects these tariffs will have on the economy could be said to be somewhat smaller. And yet the fact remains that the economy will still be dealt a considerable blow. A downward pull on real GDP of 0.55% is enough to cancel out a year’s worth of Japan’s real GDP growth.

With high prices domestically creating headwinds, given the downward effects that the tariffs will have on GDP, I would estimate there to be around a 50 percent chance that the Japanese economy will enter a mild recession phase over the next year.

Japan Agrees to Import More U.S. Goods

Japan will also be procuring several billion dollars’ worth of additional defense equipment from the U.S. per year. The U.S. media reported that Japan will be hiking its defense spending with U.S. firms from $14 billion to $17 billion a year.

Furthermore, Japan will be purchasing U.S.-made commercial aircraft, including 100 aircraft from U.S. manufacturer Boeing. It was also stated that Japan and the U.S. will be exploring the potential for a new contract for supplying liquid natural gas (LNG) produced in Alaska.

That said, certain differences in opinion are also emerging with regard to the Japan-U.S. agreement. The Japanese government explained that the purchase of several billion dollars’ worth of U.S. defense equipment per year would be carried out within the scope of existing plans, and would not constitute an additional purchase based on the latest agreement.

Japan and the U.S. View the $550 Billion U.S. Investment Plan Very Differently

According to this framework, the investments by Japanese companies in the U.S. will support those industries by way of equity investments, loans, and loan guarantees made by Japanese government-affiliated financial institutions. This fact sheet can be read to indicate that investment activities in the U.S. by Japanese firms with the support of government-affiliated financial institutions, which could place a burden on the Japanese people, are to be carried out in order to contribute to the rebuilding of U.S. industries, and moreover, this is all happening under the direction of the U.S. government and of President Trump himself.

These statements could be taken to suggest that Japan is subordinate to the U.S., and thus are at a major disconnect with the explanations given by the Japanese government indicating that the arrangement will be to the mutual benefit of both countries. It would seem that this serious divergence of opinions between the countries concerning the agreement needs to be resolved as quickly as possible.

Will This Agreement Merely Slash Japan’s Trade Surplus with the U.S. in Half?

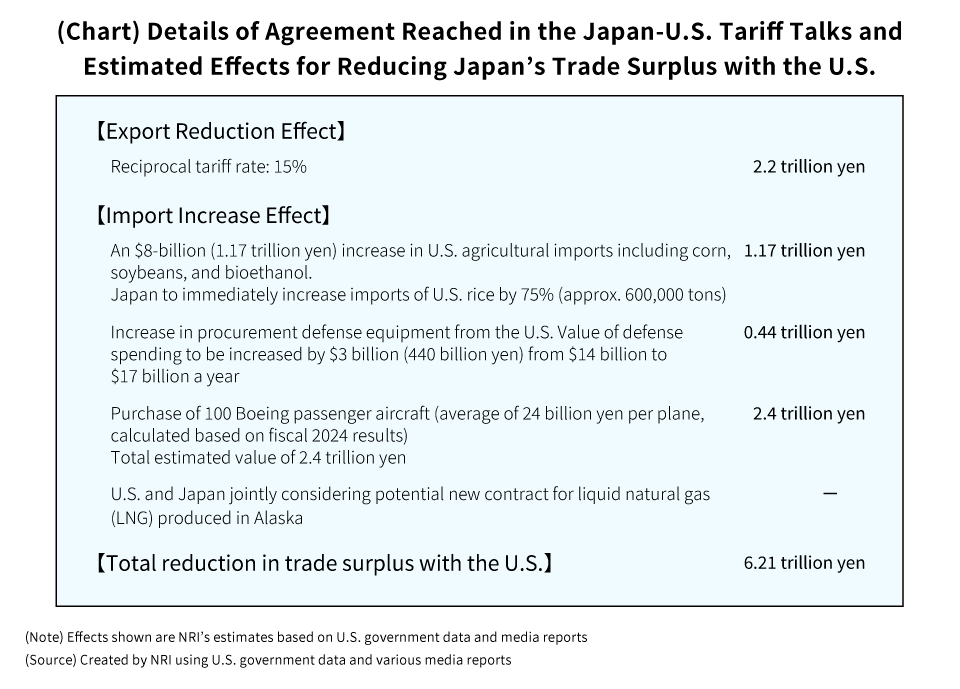

First, the 15% reciprocal tariff would reduce the value of exports bound for the U.S. by approximately 2.2 trillion yen. Incidentally, for tariffs alone to eliminate Japan’s trade surplus with the U.S., the tariff rate would need to be 60%.

The increase in imports of U.S. agricultural products would raise the value of all imports from the U.S. by 1.17 trillion yen. A three-billion dollar increase in imports of U.S.-made defense equipment would raise the value of all imports from the U.S. by approximately 440 billion yen.

The purchase of 100 aircraft from Boeing, as calculated based on fiscal 2024 results, would increase the value of all imports from the U.S. by 2.4 trillion yen.

If we combine all of those figures, this new agreement would cut Japan’s trade surplus with the U.S. by around 6.2 trillion yen, which works out to approximately 70% of the 8.6 trillion yen that was the total value of the country’s trade surplus with the U.S. in 2024 (chart). Even all of that would not go all the way to eliminating the trade surplus.

Yet since the Japanese government has explained that the purchase of this defense equipment does not represent new purchasing but rather falls within the scope of existing plans, it presumably will not serve in reducing the trade surplus with the U.S. any further. And it is possible that the procurement of those 100 Boeing aircraft has much to do with purchasing decisions made by aircraft companies prior to the Japan-U.S. agreement.

Now, if we rerun the calculations on the assumption that the defense equipment purchases will not contribute to reducing the trade surplus with the U.S., and that the new agreement is responsible for only around half of the 100 aircraft to be purchased from Boeing, then the effective reduction in the trade surplus with the U.S. resulting from this agreement would come out to approximately 4.6 trillion yen, or just around enough to cut Japan’s trade surplus with the U.S. from 2024 in half.

Thus, it would appear that even with this latest agreement, there will still be a ways to go before Japan’s trade surplus with the U.S. (or the U.S. trade deficit with Japan) is eliminated, as the Trump Administration wishes to see happen.

The Tariff Issue Will Be Sticking Around

And once the Trump Administration recognizes (as we have already seen) that this new agreement will have only a minor effect in reducing Japan’s trade surplus with the U.S., it may well move to raise the U.S.’s reciprocal tariff rates with Japan with the aim of truly eliminating Japan’s trade surplus with the U.S..

Moreover, if the Administration were to judge that Japan’s framework for investing in the U.S. differs from perceptions on the U.S. side, that could potentially destroy the agreement between Japan and the U.S. The Trump Administration has said that it will be checking on a quarterly basis to see how Japan is implementing the agreement, and that if it concludes Japan’s efforts to be insufficient, it could raise the reciprocal tariff rates to 25% after all. There is also a lingering possibility that it could demand additional measures be taken by Japan, such as implementing voluntary export restraints in trade with the U.S. or expanding imports of U.S. goods.

On the other hand, there is also still a chance that Japan may seek going forward to partner with other nations in appealing to the Trump Administration to abolish or significantly overhaul its unreasonable tariff rates. By allying itself with other countries, Japan could enhance its bargaining power vis-à-vis the Trump Administration compared to the power it has in these bilateral talks. If that succeeds, it might be able to persuade the Trump Administration to lower the tariff rate. Furthermore, if the effects of the tariffs lead the trend in the U.S. of rising prices and faltering economic conditions to become more pronounced, the Trump tariffs could face mounting criticism at home, in light of which the Trump Administration might even opt to lower the tariff rate on its own.

Thus, there would seem to be a dual possibility, that the tariff rate could either be raised or be lowered in the times ahead. What all of this does not mean is that the tariff agreement between Japan and the U.S. has reached any sort of definitive conclusion.

Profile

-

Takahide KiuchiPortraits of Takahide Kiuchi

Executive Economist

Takahide Kiuchi started his career as an economist in 1987, as he joined Nomura Research Institute. His first assignment was research and forecast of Japanese economy. In 1990, he joined Nomura Research Institute Deutschland as an economist of German and European economy. In 1996, he started covering US economy in New York Office. He transferred to Nomura Securities in 2004, and four years later, he was assigned to Head of Economic Research Department and Chief Economist in 2007. He was in charge of Japanese Economy in Global Research Team. In 2012, He was nominated by Cabinet and approved by Diet as Member of the Policy Board, the committee of the highest decision making in Bank of Japan. He implemented decisions on the Bank’s important policies and operations including monetary policy for five years.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.