NRI JOURNAL

Innovative digital magazine with insigh into society, people, business & technology, and hints for the future.

369 items

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight Into World Economic Trends: The Independence of Central Banks is Under Threat

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight Into World Economic Trends: Stablecoins and the U.S. Dollar’s Hegemony

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight Into World Economic Trends: Japan-U.S. Tariff Talks Reach an Agreement, But Negative Economic Effects to Persist

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight Into World Economic Trends: The Bank of Japan’s Plan for Scaling Back its JGB Purchases

-

Exporting Excellence: Elevating Japan’s Service Industry through AI and Innovation

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight Into World Economic Trends: Is the Trump Administration Shifting its Policy from Tariffs Toward Weakening the Dollar?

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight Into World Economic Trends: The Trump Tariffs, and Prospects for the U.S.-Japan Tariff Talks

-

The Six Intelligences That AI Will Expand and the Arrival of the AI Agent Era

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends: Shunto Wage Hikes Lack Momentum

-

How AI Will Change Japan’s Future: Exploring its Spread and its Potential

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends: One Year of Monetary Policy Normalization, and Inflation Expectations

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends: The Beginning of Trump Tariffs 2.0

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends: The BOJ’s “Review of Monetary Policy from a Broad Perspective”

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends: Trump’s Tariffs Arrive Early, and the Musk-Led Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : Correcting Tokyo’s Population Overconcentration, and Pooling Together Growth Strategies

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : Japanese and U.S. Fiscal Policies Are Moving in Opposite Directions

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : The Direction of the U.S. Presidential Election and Its Implications for the Japanese Economy

-

The Role of Companies in the Age of AI

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : The End of An Historic Yen Depreciation Phase Is Now In Sight

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : Bank of Japan Moves Toward Quantitative Tightening

-

The Outlook for Generative AI in 2024: Generative AI Shifts from “Trial” to “Utilization”

-

In the Era of Generative AI, Companies Must “Dare” to Embrace New Technologies as Growth Opportunities

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : A Weakened Yen at 1 USD/160 JPY Will Put Collaboration Between the Government and the Bank of Japan to the Test

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends : Bank of Japan Set to Break Away From Unprecedented Easing

-

Generative AI: Expanding Human Capabilities

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends:

Stock Prices Continue to Rise Amid Economic Slump -

Takahide Kiuchi’s View - “Three Tailwinds for Bitcoin, but Challenges Remain”

-

The Multidimensional Future of Humans and AI - NRI Dream Up the Future Forum: Tech & Society (Part 2)

-

Prospects for a New Society in the Generative AI Era – NRI Dream Up the Future Forum: Tech & Society (Part 1)

-

Generative AI and Soft Skills

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Will There Be a Virtuous Cycle of Wages and Prices? -

How Will Generative AI Change Business?

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Overhauling the Technical Intern Training Program ? Raising the Latent Potential of the Japanese Economy Also Possible -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Attention Gathering on Next Spring’s Labor-Management Wage Negotiations and the BOJ’s Price Stability Target -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends:

The Battle Between the Market and the Authorities Over the 1USD/150JPY Exchange Rate -

The Looming Security Risks of Generative AI, and the Responses Required of Companies

-

Prospects for Logistics Innovations and Next-Generation Human Resources

-

Will a World Dominated by Generative AI Be Good News for Humanity? ――New Society in the Generative AI Era

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The “Japanification” of the Chinese Economy and the “Chinafication” of the U.S. Economy -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The BOJ’s Policy Revisions and Prospects for Soaring Prices -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Parsing the Bank of Japan Literature for the Future Course of a Monetary Policy at a Crossroads -

Prospects for a Central Bank Digital Currency in Japan, and Three Use Scenarios for Individuals

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends:

Excessive Corporate Debt as the Achilles’ Heel of the US Economic and Financial System -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends:

Making Growing Inbound Demand the Engine for Japan’s Economic Revitalization -

Takahide Kiuchi’s View - Insight into Economic Trends: Financial Crises Appear in Different Forms at Different Times

-

Hydrogen Energy Utilization Business Accelerates Worldwide – Three Approaches to Market Entry

-

The Long Bet

-

Takahide Kiuchi’s View - Insight into Economic Trends: Ten Years of “Another Dimension” of Easing, and Policy Prospects Under the Bank of Japan’s New Administration

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Will There Be a Virtuous Cycle in Prices and Wages? -

Takahide Kiuchi’s View - Insight into Economic Trends: Making 2023 a Year of Change in Monetary Policy

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The FTX Collapse and the Demise of the Cryptocurrency (Virtual Currency) Boom -

Takahide Kiuchi’s View - Insight into Economic Trends: U.S. Economic Policy After the Midterm Elections, and a Turning Point in the Foreign Exchange Market

-

Japanese and Chinese Economic Policies in a Rapidly Changing International Environment—Lessons from the Discussion at the Japan-China Financial Roundtable

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Insight into Economic Trends: Can Foreign Exchange Intervention Halt the Yen’s Depreciation? -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Insight into Economic Trends: Three Pillars for Promoting the “Doubling Asset-based Incomes Plan” -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Insight into Economic Trends: How Long Will This Historic Inflation Persist? -

The State of Legal Reform and Privacy Investments Towards GAFA Regulation

-

AML/CFT Measures Face Growing External Pressure in Response to Ukraine Situation

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Relentless Volatility of the Cryptocurrency Market and the Future of DeFi (Decentralized Finance) -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Searching for a Turning Point in US Monetary Tightening Policies, Which Hold the Key to the Yen’s Depreciation and the Global Economy -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Does the War in Ukraine Pose a Major Risk for the Global Economy? -

Analyzing Future Work Styles from a Digital Perspective

-

Takahide Kiuchi’s View - Insight into Economic Trends:

Will a Weak Yen be Positive or Negative for Japan’s Economy? -

The New Way of Working after Covid-19

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

“New Capitalism” and “Stakeholder Capitalism” -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The 2022 Global Economic Outlook - A Focus on Soaring Prices and Normalization of Monetary Policy - -

Will Global Warming Crisis Awareness Increase Eco-Friendly Food Needs?

-

Preventing Data Scientists From Falling Into the Programmer’s Pitfall

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Growth or Distribution - Prospects for the Government’s Economic Policies After the Lower House Election -

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends:

The Normalization of Monetary Policy Around the World and Emerging Financial Risks -

NRI’s Initiatives in Sustainable Finance and Digital Currencies

-

Government-Led Vaccination Initiative is Key in Promoting Vaccination

-

Turnaround in Strategy of Alibaba, Tencent, and Ant Group and its Background

-

The Fruit of Hope Growing at the Edge of Civilization

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends:

What is the Appropriate Way to Handle the United States’ Monetary Risks? -

What Kind of Future Do We Envision with Digital Government and What Kind of Social Change Will Be Created?

-

IT Roadmap 2021: Exciting Changes in Information Technology over the Next Five Years!

-

Furthering Opportunities for People with Developmental Disorders in a Digital Society, and the Economic Impact

-

Why Assistance Is Not Reaching People Who Are “Substantially Out of Work” --Challenges and Solutions

-

A Spirit of Challenge and Readiness for an Age of New Normal

-

Why Have China’s Digital Society Initiatives Been Successful?

-

Service Innovation from Digital Technology--Through the Realization of High-Speed PDCA

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Pros and Cons of the Biden Administration’s Massive Infrastructure Investment Plan -

Utilizing “Disposable Listening Time”

Audio Media Marketing -

Trends in Digital Yuan, for Which Trials Are Underway, and the Impact on Japan

-

“Spatial Digital Healthcare” Enabling Consumers to Spend Time Safely and Securely

-Making it so that even if a virus is brought in, it cannot spread and disappears naturally- -

Robust D2C Business Demands a Innovating a New Kind of Customer Experience That Cannot Be Captured by the Term “Direct Sale”

-

“Zero Trust” Supports Remote Work

-

Digitalization and Local Revitalization

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

“Negative” Interest Rate Increases and Hopeless Financial Policies -

Retail Robots: The Trump Card for Solving Labor Shortages and Expanding Business Opportunities –Turning Stores into Vending Machines–

-

Numbers of Women Who Are “Substantially Out of Work” and “Isolated from Assistance” Increasing Dramatically During the Covid-19 Crisis

-

A Prosperous Society Beyond “After Covid”

-

The Reality for Japanese Companies as Seen in the 2020 Fact-Finding Survey on Information Security

-

“IT Navigator 2021” – Forecasting Market Trends up to FY2026

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Individual Investors Shake Up the US Stock Market -

hyphenate×NRI: A Fusion of Design and Business Supporting Value Creation and Transformation

-

Towards an Accurate Understanding of the Reality of Workers Furloughed Because of Covid-19, and Truly Necessary Employment Policies

-

Cyber-Attack Trends and Key Points for Countermeasures as Seen from the Front Lines of Security Log Monitoring

-

Achieving Smoother Communication and Higher Productivity in Remote Work

-

Three Steps to Developing Digital Talent: In-House Talent Essential to Successfully Compete in the Digital Age

-

Communication Strategies for Managers

-

Changing Advertising with Data (Part 2) –The Belief Behind the Launch of the New Business “Insight Signal”

-

Changing Advertising with Data (Part 1) –The Belief Behind the Launch of the New Business “Insight Signal”

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Another State of Emergency Declared Makes for a Tough Start to the New Year -

Possibilities for the Post-Corona Society and Economy: NRI Dream Up the Future Forum 2020

-

Impact of Covid-19 on the Japanese Economy and Measures to Avoid Bottoming Out

-

Aiming to Become a Business that Creates Social Value

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Hoping for a Transition to Economic Policies on the Offensive in 2021 -

The New Normal Company -- The Ability to Continually Transform to Survive an Era of Drastic Changes

-

Shiseido x NRI: A Place for a New Brand Experience that Fuses Human Touch with Digital Technology Has Opened

-

A Better Future for the Post-Corona Era Created through Digitalization of National and Local Governments

-

A Pioneer Seriously Taking on the Challenge of Realizing a Digital Society Through Digital Government

-

What Type of Leadership Does the Coronavirus Pandemic Demand?

-

Towards Workstyle Reforms in Japan and Female Workforce Engagement After Covid-19

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Risk of Unprecedented Chaos Following the US Presidential Election -

Supporting Digital Transformation with a Distinctive Approach: In Pursuit of IT Environments with Superior Cost Effectiveness and Visibility

-

Impact of Covid-19 on Dining Out, Entertainment, and Travel-Related Consumption and Prospects for a Recovery in Demand

-

Creating Attractive Cities with XR Technology and Art -- Conveying Next-Generation Value at Yokohama Triennale 2020

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Supply-Side Economic Policies are Vital -

In View of the “System to Extend Employment until Age 70”, What Does the Post-Baby-Boom Generation Think About Work?

-

Topics and Measures for Residents to Make Appropriate Evacuation Decisions in Heavy Rain Disasters

-

Society 5.0 and Cyber Security

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Would a Biden Administration Mean Major Changes to the Business Environment for US Companies? -

Digital Ideas vs. Implementation Approaching a Second Stage

-

Resilient Smart Cities: Towards Realizing Safe, Comfortable Cities in an Era Living With COVID-19 and After COVID-19

-

Digital Social Capital: Towards a New Normal Brought About by the Covid-19 Pandemic

-

Secure Multiparty Computation: The Key to the Future of Digital Capitalism

-

The Telework Security Demanded by the Post-Corona World

-

New Styles of Consumption Created in Digital Society

-

Technologies that will Drive the Post-Corona Digital New Normal

-

What Does “Japan-Style DX” Look Like?

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Japan’s Economic Downturn Heads into its Second Phase; Will Recovery Be U-Shaped or L-Shaped? -

Promoting Telework with Proper Document Management -- Avoiding the Risk of Information Leaks with Digital Technology

-

The Future of Management Paved by “Online Officer Retreats” -- 25 Idemitsu Kosan Executive’s Online Endeavor

-

Measures Taken by Financial Institutions Against Financial Crime -- Fulfilling Social Responsibilities Through Proactive Digitalization

-

What Challenges do Companies Face in the Digitalization Execution Phase?

-

A Strong and Flexible IT Infrastructure that Supports Society -- Efforts for Sustainable Quality Maintenance

-

The Digital Wealth of Nations and Regional Revitalization

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Unprecedented Deterioration of Domestic Hiring Conditions is About to Become Serious -

Why Do Companies Support Sports? -- The State of Support Seen from Questionnaire Survey

-

CX in the DX Era: All Industries Will Become Service Industries

-

The Cloud as Seen from the Land of the Shikinen Sengu Ceremony

-

NRI Members Aiming to Help Restaurants Struggling During Covid-19 Selected Among Top Five in Global Hackathon

-

To What Extent Can Quantum Computers Change Business? -- Optimizing the Future

-

In Pursuit of a World-Class Japanese-Style Platform Business -- Two Platform Strategies

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Extended State of Emergency Necessitates More Funding for Additional Fiscal Support -

Creating a New Future with AR Solutions -- The Challenge of KDDI Digital Design

-

What is Needed to Expand Business in Japan’s Senior Market? Part 2: Creating Business Opportunities with Synergistic Approach

-

What is Needed to Expand Business in Japan’s Senior Market? Part 1: Gaining a Detailed Understanding of and Appealing to Seniors’ Needs

-

DX Achieved Through Passion and Patience

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Japan’s State of Emergency Declaration and Emergency Economic Measures -

The Current State of AI and its Use in Business

-

Training Digitalization Promotion Leaders -- Creating Companies with High Digital Literacy

-

Formulating Strategies Incorporating the Risks and Opportunities of Climate Change -- Long-term Visions Described by Scenario Analysis

-

Toward the Realization of Agile Enterprise -- Promoting DX Through Agile Development and Breaking the “2025 Digital Cliff”

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The novel Coronavirus is shaking up global financial markets -

The Natural Language Processing Technology that Supports TRAINA, and its Possibilities: Changes to Contact Centers Brought on by AI (Part 3)

-

Supporting a Worker - Friendly Workplace with TRAINA: Changes to Contact Centers Brought on by AI (Part 2)

-

The Challenges and Importance of Contact Centers as “Corporate Faces” in the DX Era: Changes to Contact Centers Brought on by AI (Part 1)

-

The Possibilities of ID Management in a Digital Society

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Heightened Risks to the Japanese Economy from COVID-19 -

The Success or Failure of DX Hinges on Data Management

-

Tri Petch Isuzu Sales x NRI Thailand x Brierley Japan: Committed to Increasing Customer Loyalty in the Thai Automobile Market

-

Stress Reduction through the Utilization of Virtual Reality (VR)—Enhanced Relaxation and Energy Brought on by Virtual Space Experience

-

The “Dejima” Strategy for Promoting Open Innovation in Companies: Creating an Investment Return Framework, Not a Cost Center

-

Introducing the Postmodern ERP We Need -- An Evolving ERP and Challenges for Japanese Companies

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Economic Risks for 2020 Shifting From the US-China Trade War to the Middle East -

“IT Navigator 2020” - Forecasting Market Trends up to FY2025

-

A Look at NRI’s CX Index and CX Management Methodology for Helping Japan’s Financial Institutions Promote and Establish “Customer-Centric” Business Operations

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Outlook of the Economic Recession in Japan and the World in 2020 -

Essential Security Strategies for Digital Transformation

-

The Direction Countries and Companies Should Take in the Digital Era: NRI Dream Up the Future Forum 2019

-

Why Japanese Companies’ Innovation Activities are Struggling in Silicon Valley and How NRI’s “CAMPS” can Help

-

E-commerce Business in China: What Should Japanese Companies Do to Increase their Presence in the Market?

-

Solving Social Issues as Growth Drivers

-

Eliminating Food Losses through Digital Food Chain

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Struggling Plan to Launch Libra and Battle for Currency Supremacy -

Information Security Required in the DX Era

-

Creating a New Spatial Value with 5G x XR

-

Releasing the Working Generation from Constraints for the Sustainable Future of Japan

-

The Purpose of Digitalization

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Why the Japanese are Apprehensive about the Yen’s Appreciation -

Evolving Cloud Services and Changing Awareness of Companies

-

Information Security Risks and Countermeasures in the Age of Multi-Cloud

-

Changes in the Employment Needs and Attitudes of the Elderly: An Information Base Supporting Diverse Working Styles

-

Japan’s Future Path in the Digital Transformation Era

-

Proposals for Digitalization of Society and Industries

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

China to Launch a Central Bank Digital Currency in Response to Libra -

New Value Addition with Operating Company Finance 3.0

-

“Zero Trust”, the Next-Generation Security Model Supports DX and Work Style Reforms

-

The Role of Management in Digital Transformation

-

Document Management that Guarantees Protection of Companies and Ensures the Quality of Products and Services

-

Information Security as a Management Strategy in the DX Era

-

How Will Businesses Change with 5G?

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

How will Central Banks Around the World Deal with Libra? -

What is a Successful “aaS” (as-a-Service)?

-

5G as a Turning Point (Fifth Generation Mobile Communications)

-

Global Expansion of CASE Business and Problems Faced by Japanese Companies

-

Chinese Tourists’ Behavior as Seen Through the Use of "Nitori Public × NRI" DX service: Connecting Behavior History to Hokkaido's Tourism Marketing

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Impact of the Approaching Consumption Tax Hike -

Shortage of IT Human Resources in the Digital Era

-

Personal Data Utilization Strategy in the Data Economy Era: Using the Amendments to the Act on the Protection of Personal Information as an Opportunity

-

"Share the Next Values!": Realizing the NRI Group's "Dream Up the Future" and Sustainability Management

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

"Has Japan fallen into a recession?" -

Smartphones and Uncommunicative Families

-

Changes in the Chinese Distribution and Retail Industry: From Focus on Expansion to Pursuit of Quality

-

New Trends in Personal Information Management and Information Security

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Trap of Bilateral Trade Negotiations -

Leveraging the Strengths of Japanese Companies to Lead Smart Cities with “Digital General Contractor” Functions

-

IT Roadmap 2019: Recent IT Trends and Future Forecasts

-

Creating New Experiences at Service Stations by Using Digital Technologies: Showa Shell Sekiyu’s "Shell CONNECT"

-

How to Achieve Social Value Along with Economic Value: Rethinking Management Plans from a Long-Term Perspective

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Potential of Dynamic Pricing -

Information Security Required for a Safe and Secure Mobility Society: The Role of NDIAS’ in Ensuring Quality in the Automobile Industry

-

How to Survive in the Era of Digital Capitalism

-

Technium’s New Business Model: Becoming a "New Partner" Supporting Machine Tool Customers

-

Cultivating future security professionals for a resilient infrastructure

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Why can the longest postwar recovery not be felt? -

Drawing out the strength of engineers: The challenge of bit Labs

-

Will salaries soon be credited through “xx pay”?

-

Competitive advantage of digitization: Suggestions obtained from financial cases

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Development of international rules for data distribution led by Japan -

Agile Development in the DX-age enabled by bit Labs: What engineers call “a change of mindset”

-

Companies’ approach to public clouds

-

ASG helps Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) renew its complex system environment and drastically improves work-efficiency

-

“Encryption Key Management”: Supporting Information Security in the Digital Era

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - “Trade issues pressuring Japanese economy in 2019”

-

NRI’s Digital Business Strategy

-

Casual meetup providing a “Platform to foster innovation” - NRI Hackathon 2018 bit.Connect

-

The Heisei Era and Beyond as Understood from NRI’s Publications

-

“IT Navigator 2019――Forecasting Trends up to FY 2025”

-

Work-Style Reform and Digital Workplaces

-

Cultivating ideas to generate new value――Implemented by bit Labs

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

“Concerns when preparing for an economic recession” -

Era of “nonmarket strategy” experts: New ideas to transform the business environment are the key to overseas expansion

-

Introducing the society aimed through digital capitalism: NRI Dream Up the Future Forum 2018

-

Overseas M&A based on growth story

-

Changing human resource strategies through HR technology in the age of increasing job mobility

-

Strengthening “Health and productivity management” -- “Visualization” of effects through proper collaboration

-

Future Working Style Ushered in by the Digital Workplace

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View―― TPP that will come into effect within the year and US trade policy post midterm elections

-

Advantages and Security Risks Associated with the Spread of RPA

-

A Rethinking of Digitalization and Knowledge Management

-

Bringing the Fruits of Global Economic Growth to Japan’s Household Income through Effective Utilization of Financial Assets

-

A Pioneer in Operations Management

-

Nurturing Personnel who can Take Charge of Information Security in the Future “SANS NetWars Tournament”

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Prospects for the International Trade System, and Japan’s Role

-

Creating Digital Businesses that Engage with Customers—The Necessary Perspective for Digital Transformation

-

Bringing A “Digital Revolution” To Japan

-

How Different Industries Will Face Digital Transformation

-

Shiseido Japan × NRI Combining Cutting-Edge Skin Science and Technology

-

How Should Companies Face the Growth of ESG Investments? — The Required ESG Approach and Information Disclosures to Investors

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Japanese Government and the Bank of Japan Must Take the Lead in Bringing About a Cashless Society -

Purpose-Focused Management Leads to Swifter Strategy Execution

-

The Three Changes That Digital Capitalism Will Bring About

-

New Alternative Investment Method Created With Combination of Real Estate, Finance and IT

-

The Way of Reforms: Trust-Based Management

-

Transcend Intra-Company Barriers and National Borders with Digital SCM Reforms

-

Utilizing accumulated knowledge to do work that stands the test of time

-

What Should Japanese Companies do with the GDPR?

—Protecting Personal Information in a Digital Age Without National Borders -

Dedicated to one path as a leader in consumer behavior surveys

-

With Serious Worker Shortages, Construction Sites Need Drastic Improvement in Productivity

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Will the Bank of Japan Reinforceon its De-Facto Normalization Policy? -

What Kind of Business Management Leads Directly to Corporate Growth?

-

Putting Loyalty Marketing into Practice

-

What Does It Take for Open Innovation to Create Successes?

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Escalation in U.S.-China Trade Frictions Seen Rocking Global Economy -

How Digital Capitalism Will Shape Our Future

-

An Approach to Achieving CX/UX in the Digital Age

-

The Future That DX Will Bring Part 2 Economic Bloc Partnerships Creating New Value

-

The Key to DX Success Lies in Management’s Vantage Point

-

The Future That DX Will Bring Part 1 KDDI Digital Design Taking on a Challenge

-

A Different Kind of IoT Security ― Safeguarding Industry 4.0 from Cyberattacks

-

What Can A Non-Touch “Floating Display” Do? Floating Display at Japan Football Museum Shows Us The Future

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Are the Effects of the Planned Consumption Tax Increase Being Overestimated? -

The Advantages of Visualizing Your Security Measures

-

Toward an Era of Active Participation by Disabled People in Convenience Stores

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

The Potential of Virtual Currencies as Investment Vehicles -

Does Seeing Athletes Do Well Make People Happier? Corporate Sports Survey Finds Changes in Public Opinion

-

The Insurance Systems in the Cloud Computing Age

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Are Japan-U.S. Trade Frictions Set to Heat Up Again? -

Will “Information Banks” Find Acceptance Among Consumers?

-

The Key to succeed CX strategy

-

Commitment to Adapting to Paradigm Shifts

-

Taking on The Challenge of DX2.0

-

Mining A Diamond in the Rough Final Report on the Young Professionals Study Group on Business Process Innovations with Nomura Securities

-

What is a True “Work-Style Reform”

-

How Public Participation Can Help Maintain and Revitalize Japan’s Regional Railways

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

On the Advantages of a Cashless Payment -

Analytics as a Source of Competitive Advantage for Companies―Two Key Points for Producing Results

-

Digitalization and Corporate Management

-

Higher Statutory Employment Rates to Result in Diversification and Sophistication of Employment of Persons with Disabilities

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Will Corporate Debt in Emerging Nations be the Next Global Risk? -

Skills required of project managers for large-scale projects (Part two): How to communicate

-

Protecting Our Motorized Society from Cyber-attacks

-

Skills required of project managers for large-scale projects (Part one): High level of professional skill

-

How to manage digital labor: What is the key to utilizing RPA?

-

What is sustainability management and why is it indispensable for sustainable growth?

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Market adjustment = The pitfall of the 2018 world economy -

On productivity improvement

-

Protecting our motorized society from cyber-attacks

-

30th anniversary of the NRI merger: Towards a quantum leap

-

NRI Business IT

Real estate crowdfunding: Creating innovation with clients -

Bringing innovation to advertisement through single-source data

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

What does it mean to “exit deflation”? -

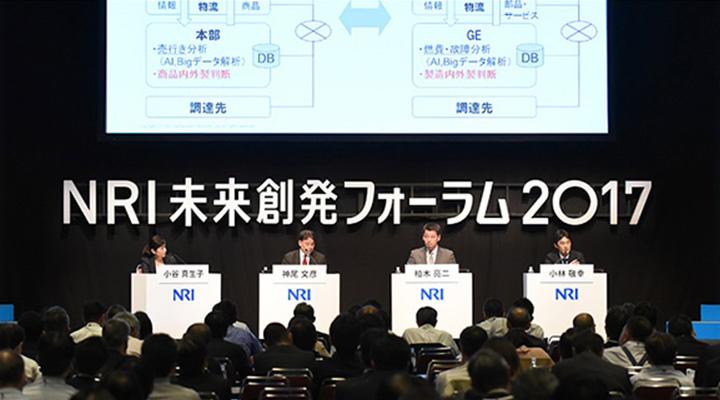

Digital opening in the near future: NRI Dream Up the Future Forum 2017 (Part two)

-

Quality control for companies in the digital age

-

Digital opening in the near future: NRI Dream Up the Future Forum 2017 (Part One)

-

A new form of industrial infrastructure that connects people and companies: How should Japan utilize MICE?

-

The future of the healthcare industry with digitization

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Policies for raising economic potential instead of increasing wages -

Clouds and crowds: Foreword to the September issue of Knowledge Creation and Integration

-

Promoting Mutually Beneficial Africa-Japan Relations

-

How to effectively adopt RPA and operate without failure

-

What is required to adopt agile development at Japanese companies?

-

The potential and security of blockchains

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View - Insight into World Economic Trends :

Evaluating the Goldilocks Economy -

The key to work style reform with AI is ongoing operation

-

Can Japanese companies utilize their strengths?

The changing face of outer space development and the expanding outer space business (Part 2) -

Improving the productivity of the service industry

-

A new era when anyone can join the exciting space business —

Changes in space development and expansions in space business (Part 1) -

The potential of Bitcoin—Beyond an investment opportunity and payment platform

-

What is the role of the IT department in an era of digitalization? From the results of 2016 "Survey on the Status of IT Use in User Companies" Part 2

-

How Do Consumers View FinTech-Related Services?

-

To Create a Society Where Everyone Can Be Independent

-

How rural cities in Japan can connect globally as rural hubs

-

Childcare for 886,000 more children by 2020 to compensate for the diminishing workforce

-

Why NRI offers reconstruction aid for the Kumamoto prefecture earthquakes

-

Enhancing the Health of Workers Through "Collabo-Health"

-

On the digitalization of Japanese companies: From the results of 2016 "Survey on the Status of IT Use in User Companies" Part 1

-

Differences in work styles help generate ideas: Mid-term report on youth study group with Nomura Securities

-

The predicament of Japan's logistics industry

-

Data scientists who understand business

-

Chinese internet services are a business opportunity for Japanese companies

-

Overcoming a fear of AI to achieve "AI for your life"

-

CIAM to enable general consumers to safely use services

-

The individuality and human resource diversity required in the age of AI

-

An overseas joint venture strategy that considers future separation

-

How do we protect against security threats to the things we use in our everyday lives?

-

What to do about the vacant house problem in Japan?

-

Three points for the popularization of the iDeCo individual-type defined contribution pension plan

-

Is digitization making progress at Japanese companies?

-

Corporate governance reforms are gradually starting

-

Reforming the Mobile Phone Industry

-

The New Trend in Corporate Management is CSV

-

How will AI change business?

-

Mobile Technology Contributing to Paperless Meetings

-

Two Perspectives That the Global Strategy Requires

-

Four Years of Change as Seen from NRI’s “Year-End Consumer Internet Survey”

-

NRI + Nomura Securities = Youth study groups towards business process innovation that utilizes digital technologies

-

How Far Will Services for Point Program Members Evolve?

-

“NRI’s Future Timeline”: Predicting the Future Up To 2100

-

Five Advantages to Considering Employee Health in Company Management

-

“Industry4.0” As a Break from Mass Production Manufacturing

-

Keeping the Supply Chain Moving

-

Three Essential Features of IoT

-

The strategizing of integrated-career women as the foundation of corporate competitiveness

-

Three barriers to clear for open innovation between startups and major corporations

-

“Real Estate Tech” Will Change Conventional Wisdom About Housing

-

Why FinTech Matters to You

-

Open Innovation Creates New Value in the Digital Economy Era

-

Why Sustainable Corporate Growth Should Be Viewed as a “Management Relay”

-

Cooperating with China as It Enters an Era of Qualitative Development Ichiro Kawashima, NRI Shanghai

-

How Far Will Artificial Intelligence(AI) Spread?

-

Will Japan Fall Behind in IoT?

-

What is FinTech?

-

Evolution of Digital Marketing

-

Creating a Disaster-Resilient, Community-based Region

Series

-

Takahide Kiuchi's View

Backed by his wide experience as an economist at a securities company and former BOJ board member, Takashi Kiuchi explains a wide range of topics including domestic and international economic and financial analysis, financial and fiscal policy and market analysis.

-

Featured People

Introducing NRI's top future-casting experts.